TASK FORCE OF BACON

From left to right foreground: General Walker, General Patton, and General Van Fleet

Commanding General of the 90th Division, who is shown explaining the situation at his

Command Post at Koenigsmacher. In the background are Colonel Harkins, Deputy Chief of

Staff, Third Army; Colonel Codman and Major Stiller, aides to General Patton

While this action was going on in the northern sector of the XX Corps zone, the 95th Division

increased pressure on the west of Metz. The bridgeheads at Thionville and Uckange were expanded

against bitter opposition. Small arms melees at close range were fought frequently, as the enemy

stubbornly resisted this direct threat to the inner defenses of Metz.

A strong blow was being struck against the enemy fortifications in the area around for D'Illange.

The fort was first subjected to a 30 minute barrage by several battalions of XX Corps artillery and then

assaulted by infantry carrying explosive charges of TNT. Final resistance in Fort D'Illange ended during

the morning of November 15th. Another Metz bastion had fallen to the grit and ingenuity of the XX

Corps forces.

The XX Corps Operational Reports sum up the situation: "General Walker had been studying the

situation on the eastern banks of the Moselle and had realized the military potentialities that existed in

the area, particularly since intelligence and battle report showed the enemy had been forced to withdraw

the bulk of his river line units and commit them in the zone of the 90th Infantry Division. Accordingly,

the Corps Commander decided to constitute a mobile striking force. This force would sweep the eastern

banks of the Moselle along with three to four mile zone of advance and attack Metz from the north."

The mission assigned Task Force Bacon was to drive into the outskirts of Metz in three days, sweep

south, clear the east bank of the Moselle, and attack Metz from the north. Speed and firepower were the

attributes of this force. Each town was entered with tank destroyers firing point-blank at all points of

resistance. Two 155 mm self-propelled guns were placed well forward in the column ready for

immediate use against enemy strongholds. On entering towns, marching fire by the infantry and heavy

use of the 90 mm guns of the tank destroyers quickly discouraged snipers and gun crews who either

surrendered or fled. Flank protection was provided by the wide Moselle on the right and elements of the

90th Division on the left.

|

|

Jumping off the 0700 hrs, November 16, the Task Force drove on Guenange and quickly reduced

it. The town of Bousse further south received the same summary treatment and was cleared by 0900 hrs.

Continuing the rapid pace, Task Force Bacon wrested Ay-sur-Moselle from an amazed enemy and took

Tremery before nightfall.

The drive continued on the 17th of November. A path was blasted through several more towns

until Antilly and Malroy were reached. About two miles to the south old Fort St. Julien stood squarely

astride Task Force Bacon's path into the northern outskirts of Metz. Located on high ground, the fort

commanded the two main routes into the city and was reported to be held in force by the enemy.

A plan was prepared for the reduction in this obstacle, and on the morning of November 18th,

the attack was launched after Corps artillery from west of the Moselle had hammered the fortified

position. The Task Force, after an all-day fight, had entirely surrounded the fort by dusk. After dark, a

155 mm self-propelled gun was brought up and fired point-blank across the moat at the iron gate barring

entrance into the fort. The gate collapsed after 10 rounds and the infantry raced into Fort St. Julien.

Reports received about this time related that the German garrison was abandoning Fort

Bellacroix in the eastern suburbs of Metz. The fort was quickly overrun and bypassed. As elements of

the Task Force moved on toward Metz, a terrific explosion blew up part of the fort and killingsthe road

next to it, killing eight and wounding 49 of the Task Force troops. The evening of November 18th

found Task Force Bacon extended along the railroad line in the railroad yards of Metz, ready to sweep

into the city itself at daylight.

REDUCTION OF FORTIFIED SALIENT WEST OF METZ

While some elements of the 95th Division were engaged in bridgehead operations east of the

Moselle, the remaining elements were gradually drawing a ring around the strong line of fortified groups

west of the Moselle on the approaches to Metz. The broad, level land behind these forts offered an ideal

tank route into Metz. The forts, however, with their heavy guns were located on steep, heavily wooded

ridges and dominated the surrounding terrain. The fortress ring had to be cracked and unhinged before

the XX Corps armor and infantry could surge into the heart of Metz.

The 95th Division plan directed two regiments to make diversionary attacks on Fort De Feves

and the Canrobert Group while the remaining regiment wheeled north behind the line of forts and then

south into Metz.

The first penetrations of the fortified positions were made quickly. Attacking early in the

morning of the 14th of November, infantry seized the high ground between Forts De Guise and Jeanne

D'Arc before noon, while another force stormed Fort Jussy (Nord) and Fort Jussy (Sud) and captured

them under intense artillery and mortar fire.

The inevitable German counterattack was a strong one and succeeded in closing behind four

infantry companies cutting them off from their main forces. For three days, artillery liaison planes

supplied the surrounded troops with food, ammunition, and medical supplies. The four companies

consolidated their positions fought off every counterattack that the Germans launched.

This seemingly unsuccessful attack was a valuable divergent that enabled elements of the 95th

Division further north to sweep around the northern system of fortified defenses. Fort De Feves was

|

|

taken by small arms fire, and the town of Feves was occupied and the German defenders chased to the

south. As the defensive crust was breaking, the 95th Division seized the high ground west of the town

of Woippy in one day and fanned out over the low ground west of the Moselle.

The disorganized Germans made the going costly but the Division’s offensive was running ahead

of schedule. The town of La Maxe was taken and fighting was raging around Woippy as darkness set in

on November the 15th.

On the 16th of November, heavy fighting went on in Woippy which was the nerve center of the

northern Metz defense. Opposition stiffened along the line, and an attack on Fort Gambetta was

repulsed with heavy losses, but the Canrobert Group was successfully contained by Division forces.

By the morning of the 17th of November, German resistance began to crumble. Strong XX

Corps columns east of the Moselle were already closing in on the city of Metz. Two full regiments of

the 95th Division had succeeded in driving deeply behind the main line of forts protecting Metz from the

West. The northern segment of the Metz defensive line had been shattered and the majority of the

fortified groups were in the hands of XX Corps.

At midday on the 17th of November, XX Corps alerted agents of the Free French Forces of the

Interior, by a prearranged radio code signal, to stand by to seize the switches controlling the demolitions

which the enemy had placed on the bridges crossing the Moselle at Metz. Orders were issued by

General Walker to the 95th Infantry Division to launch an all-out effort to drive into the city and seize

bridges intact.

During the early morning hours of the 18th, patrols along the western side of the river could see

huge fires raging in Metz. Just before dawn a series of heavy explosions rocked the city. The Free

French Forces of the Interior had failed to reach the control switches and the Germans were blowing the

Moselle bridges, abandoning the troops still garrisoning Fort Driant, Jeanne D'Arc, Plappeville, and San

Quentin on the west side of the river.

The 95th Division began its final assault on Metz on the 19th of November. Using captured

canoes and barges as well as their own assault boats, troops crossed the Moselle to the island formed by

the Moselle River and the Metz Canal and quickly cleared it of the Germans. Driving across the canal,

they pushed on rapidly to clear three city blocks. Under heavy artillery and machine-gun fire from Forts

Driant and San Quentin, another task force struck across the river and began the fight for the

northeastern section of the city where the German garrison was under the personal command of

Generalleutnant Kittel.

CLOSING IN FROM THE SOUTH

While these steady gains were being made on the north and west sectors of the XX Corps front,

the 5th Infantry Division was surging up from the south converging swiftly on the city of Metz.

The 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division, in an attempt to halt the advancing Corps drive from the

south, formed the switch line on Fort L'Aisne extending to Sorbey. A strong combat patrol was sent to

check on the strength of the garrison in Fort L'Aisne on the night of the 10th of November and

surprisingly found this strong fortification manned by only a few stragglers. It was learned that the elite

|

SS Garrison had withdrawn in order to be relieved by a fortress machine gun battalion, but the patrol

had reached the fort before the relief was affected. The fort was immediately secured in strength.

Fort L’Aisne, south of Metz, captured while awaiting next relief.

Another attack was made on the river line west of Metz on the morning of the 18th. Forts

Kellerman and La Caene were occupied and the huge Fort Plappeville was contained. An effort was

made to seize intact the bridge that spans the Moselle to the Isle De Symphorien, but the bridge was

blown as a leading platoon was in the act of crossing, and eight men of the patrol were killed. The entire

95th Division was now drawn up near Metz for an assault into the city.

With the fortunate fall of this critical fortress position, the German switch line was unhinged, and

General Walker decided to take prompt advantage of this opportunity to make a straight thrust into the

city of Metz through the fortress system. The 5th Division was ordered to make a close-in encirclement

of the city.

The division moved swiftly north in a series of rapid movements, meeting sharp but scattered

resistance. The fortresses, when encountered, were first enveloped and then combat patrols were sent to

probe their defenses. In most cases it was found that the garrison had withdrawn and none of the forts

had to be taken by assault. To speed the advance, the entire strength of the 5th Division was committed

on the 16-mile line.

The Operational Reports of the XX Corps describe the general situation as follows: "The

principal problem was to get into Metz before the majority of our fighting troops were evacuated

because of trench foot and exposure. All during the operation until the 14th, there had been continuous

rain, and the night of the 14th rain turned to snow and sleet, covering the ground to several inches by

daybreak. The wet, swampy ground canalized all motor traffic to roads. Entrenchments soon became

flooded. In spite of every effort to shelter troops during pauses in the advance, to issue them dry

footgear, it was estimated that 40 per cent of the initial strength became casualties to trench foot, and

under these conditions it entailed a continuous effort of leadership to keep the attack going. The terrain

itself was not favorable, the large expanses of open ground offered no natural cover, and the constant

|

|

threat of a sudden defense from the forts, and the calculated small but sharp delaying actions

commanding ridge lines and towns constantly threatened the advance."

While the southern defenses of Metz were beginning to collapse under the pounding of Corps

forces, strong elements of the 5th Division held the Nied River bridgehead against the 21st Panzer

Grenadier Division. Elements of the 5th Division were also engaged in containing the Sorbey Forts,

which were strongly held by the Germans, and the fortified Group La Marne which was one of the

largest fortress groups in the entire Metz area. These bastions protected an escape route for the Metz

garrison.

After a sharp fight, the men and the tanks of the 5th Division forced the surrender of the garrison

of the Sorbey Forts on November 16th.

The fortified Group La Marne still stood in the path of the northward racing troops of 5th

Division and seemed to be a likely rallying point for the German troops who were now falling back on

Metz in confusion. The tremendous walls and casemates of the fortified group, if strongly held, would

form a tough barrier. In a quick maneuver XX Corps troops were relieved from the Nied River

bridgehead to storm this fort. The vital bridgehead zone was turned over to the 6th Armored Division.

During the 18th of November, Fort La Marne was contained on two sides. Infantry assault teams gained

entrance into the interior and the small garrison surrendered without firing a shot.

With the collapse of this great stronghold it became clear that the enemy defenses east of Metz

had crumbled with the speed and power of XX Corp armor and infantry and the terrific pounding of the

Corps artillery. The 5th Division infantry began now to seize fort after Fort in lightning thrusts. After

the fall of Fort Lauvalliere, roadblocks were set up cutting off all the roads from Metz to the east.

German columns, attempting to flee to the Saar, were stopped and destroyed by the air squadron

supporting the drive of XX Corps. In the triangle between the Moselle and the Seille Rivers, the enemy

put up a more effective resistance. In this area, the Verdun forts still sheltered a strong defensive force

and slowed the advance. A heavy pounding by Corps artillery and fighter-bombers failed to reduce the

strong points. No attempt was made to force an entrance into the fort since orders were to bypass them.

The city of Metz was the objective now. Casualties from trench foot were mounting. One battalion, for

example, reported that 70% of its casualties were from this source. The sweeping advance to the north

went on steadily and Fort St. Privat and Verdun were surrounded. By the 19th, units of the 5th Division

were fighting in the suburbs of metz and were strung along the railroad tracks waiting contact with the

95th Division that was to clean out the heart of the city.

The situation at this point is briefly described in the Operational Reports of the XX Corps: "By

noon of the 19th, the 95th Division on the north and west and the 5th Division on the south and east had

cleared the outlying parts of the city of Metz. What remained was the core of the city enclosed within

canals, the Seille River, and major railroad lines. The 90th Division had taken position astride the

escape routes east of the city, just west of Boulay, and was assembled with an all-around offense

awaiting the clearance of Metz.

"During the day, 5th Division troops mopped up around Fort Privat and threw a ring around Fort

Quelleu. On the 20th a strong force moved across the Seille, cleared part of the town, and captured the

railroad yards. That afternoon, the 95th Division pushed more troops across the Moselle into the heart

of Metz under heavy harassing fire from Forts Driant and San Quentin."

|

|

As more and more Corps columns moved into the city, they encountered stiffening resistance

from pockets of German troops personally directed by General Kittel, commander of the Metz Garrison.

The barracks area northwest of Metz proper was swarming with snipers and machine guns.

Throughout 20th of November, mopping up of the "die hard" resistance continued, as several

linkups were made by Corps columns driving into the center of the city from all directions. Remnants of

the once powerful Metz garrison were driven into the ever smaller pocket formed by the barracks and

military buildings on the islands in the Moselle River. There, encouraged by the presence of General

Kittel, a few hundred held out until the afternoon of the 21st, when the Metz commander was wounded.

On the morning of the 22nd, a shower of mortar shells and hand grenades routed out the last

stubborn groups of the Metz garrison. The city was reported entirely clear at 1435 hours on the 22nd of

November, 1944.

The bypassed forts, Jeanne D'Arc, Driant, Plappeville, San Quentin, Verdun, and St. Privat were

strongly held by some 2000 men still supplied with food and ammunition. The 5th Division promptly

took over the city of Metz and laid siege to the resisting forts.

The fall of Metz marked a great milestone in the historic route of the XX Corps. The courage

and fighting qualities of the XX Corps troops had resulted in a smashing of another "hold or die", Hitler-

inspired defense system. The loss of Metz and its encircling rings of mighty forts, and the breaching of

the Moselle along a broad front, though at one of its highest flood stages in history, spelled a major

disaster for the German war machine. The months of planning by the Corps staff and the daring but

accurate decisions had paid off once more in great triumph. The 1500-year tradition of inviolability of

the citadel of Metz was destroyed for all time.

In losing Metz, the German Armies lost strategic hinge on which they had hoped to anchor their

line on the Western front. Before XX Corps now lay the German border and the Siegfried Line. The

battle for France was drawing to an end, a fatal end for the Nazis. Corps columns were already

pounding their way to the Saar. The opening rounds of the Battle of Germany were beginning.

The fall of its last great stronghold in France was, moreover, a stunning psychological blow to

the German state. Metz was more than a great armored shield against the hammer blows of the XX

Corps. It was an historic symbol of victory in arms, a good luck talisman for victorious armies through

centuries of war-torn history.

The XX Corps conquered Metz at a time when every factor of weather, terrain, and supply

favored the defenders. "General Mud and his Lieutenants Rain, Snow, and Cold" were aligned on the

side of German arms. Trench foot was an ever present specter sitting alongside the "Doughs" in their

flooded foxholes; and, as the dreary, wet November days wore on, the Lorraine region, lived up to his

reputation as the rainiest in France. The XX Corps, limited as it was in many important supply

categories, notably heavy caliber ammunition, faced a foe well supplied with food and shells behind his

steel and concrete fortification and under orders from his "Fuehrer" to live or die for the Fatherland.

The bridging of the swollen Moselle River under the bellowing guns of the great Metz forts was

an engineering feat of the first magnitude, while the sweeping encirclement of the huge forts and their

systematic reduction was a triumph of tactics on the part of the XX Corps.

|

|

Successful completion of the campaign had its aftermath of ceremonies and formations. This was a great

climax to the years of preparation by XX Corps. The liberation of the historic city of Metz brought further honors

to the Corps which already carried the famed battle streamers of Verdun, Chateau-Thierry, and the Marne.

On the 29th of November, the French Government bestowed high tribute on General Walker when he was

made a member of the Legion of Honor, Officer Class, at a great civic ceremony staged in Metz.

At the same time, General Collier and Brigadier General Julius C. Slack, XX Court Artillery Commander,

received the Legion of Honor, Knight Class.

Major General Andre Dody, Military Governor of Metz, made the awards in the Place de Republique

were thousands of people had gathered to witness the proceedings and cheer the parading troops of France and the

United States. These were the first American troops to be so honored by the French Government.

Massed standards and banners of XX Corps divisions and regiments headed the big parade and review

which was taken by General Walker. French and American military bands provided the music, and the rumble of

artillery fire in the distance provided additional sound effects.

Front line troops of XX Corps who participated in the capture of Metz were heartily applauded by the

populace. French Regular Army troops who took part in the parade made a fine showing.

After the general officers had received their decorations, the award of the Croix de Guerre with Palm was

made to Colonel Charles G. Meehan, Captain David W. Allard, Sgt. S. Bornstein, Captain Guy de la Vasselais,

Lt. Col. J. W. Libcke, and Col. H. R. Snyder received the Croix de Guerre with Gold Star, Lt. Jacques Desgranges

was given the Croix de Guerre with Silver Star, and the same decoration with Bronze Star went to Tech. Sgt.

Donald Post, T/4 Denver Grigsby and T/4 H. J. Schonhoff.

The demonstration at Metz took place a week after General Walker officially turned the city over to the

French, following its capture by infantry and armored divisions in two weeks of hard and bloody fighting. Hailed

by the press of Metz as the "Conqueror of Metz", General Walker was warmly received by the people of the

liberated city.

At a formation held the next day at Corps Headquarters, General Collier made further awards to officers

and men of the XX Corps.

The Croix de Guerre with Palm went to Colonels R. John West, Henry M. Zeller, Joseph Shelton, Chester

A. Carlsten, and William B. Leitch. Receiving the Croix de Guerre with Gold Star were Colonel William H.

Green, Lt. Col. Melville I. Stark, Lt. Col. Joseph Cowhey, Lt. Col. Napoleon A. Racicot, M/Sgt. John Taylor, and

M/Sgt. Van K. Barre. The Croix de Guerre with Bronze Star was given to First Sgt. Alexander Berg, Tech Sgt.

Roy S. Hahn, and press T/4 Clarence La Pierre.

ACTION IN THE NORTH

Important as was the fortified region of Metz in the strategic aims of XX Corps and Third Army,

it was still only a part of the larger effort to fight on through the Siegfried Line to the Rhine. Once

again, as it did during the breakthrough from Normandy, the "Ghost Corps" demonstrated its ability to

fight on more than one front. While Corps forces were ringing the city and besieging remaining forts,

the forward drive to the Saar River never lost its momentum on the north flank of the Corps zone of

action where the 3rd Cavalry Group and the 10th Armored Division were operating out of the

Koenigsmacher bridgehead.

|

|

The 3rd Cavalry Group had served as the eyes of the Corps, during a seven-week river watch

along the Moselle, and was continuing to report details of enemy movements, to locate minefields and

strong points for the assault troops, and to protect the north flank of the Corps along a broad front. Now,

reinforced with tanks and tank destroyers, engineers and artillery, it was organized into Task Force Polk

under its commanding officer, Col. James U. Polk, and was assigned by XX Corps the mission of

reaching Saarburg, some 20 miles northeast through hostile territory. Further south, the 10th Armored

Division was to strike for the German border in an effort to seize intact a bridge over the Saar at Merzig.

Task Force Polk, though lightly armored, used armored tactics whenever possible in its advance

to the north. The cavalry by a series of dashes, lightning changes of direction, and sometimes plain,

ordinary bluffing, ran the gauntlet of enemy strong points while acting as spearhead reconnaissance for

XX Corps, the most mobile Corps in the Third Army. Instead of barging head-on into centers of

resistance, the XX Corps cavalry preferred more startling entrances from the flanks and rear, coming

through farmyards, barns, or even stone walls. This unit made such frequent use of secondary roads that

it was sometimes called the "Cowpath Spearhead."

Using Jeeps, armored cars, assault guns, and tanks and wild, unpredictable cross-country tactics,

XX Corps cavalry kicked up such a fuss that the Germans thought it represented at least an armored

division. With these "blitz" tactics, some cavalry units were put across the German border near Perl, and

were possibly the first Third Army troops to set foot on the soil of the Third Reich. Making full use of

the attached tank destroyers and an entire field artillery battalion, the cavalry harried the Germans,

driving them further north and east, and shortly an entire squadron had closed across the German border.

Troops of XX Corps who expected a vast change after the German border was crossed were in

for a surprise. Everything seemed the same. The people, who had been handed back and forth between

warring powers for hundreds of years, looked much the same. Both the French and German tongues

were spoken with equal fluency. But the American soldiers knew that they had "liberated" their last

town, that they were now fighting in the role of conquerors, and that their letters home would now be

prefaced "Written in Germany". The fighting, too, reached at new high in intensity as XX Corps slashed

deeper into the heart of the Third Reich. The desperate Wehrmacht used every weapon in its arsenal and

every hill and town in a desperate but futile attempt to blunt the sharp instrument that was thrust at its

vitals. It fought until it was hurled, battered and bloody, back into the hoped for safety of the Siegfried

Line.

On the 19th of November when XX Corps units were entering Metz from five different

directions, the cavalry assault in the north had come into contact with the switch line fortifications of the

Siegfried Line.

The much vaunted "West Wall" of the Germans extended in depth along the eastern banks of the

Saar, and the enemy had in addition erected a switch line of coordinated, mutually supporting pillboxes

along the Saar-Moselle triangle. Superb camouflage had made spotting of the pillboxes practically

impossible from the air. Consequently, after taking Borg the morning of the 19th of November, the

cavalry had no advance warning of the line and its light tanks were stopped shortly afterwards. Colonel

Polk at once ordered the entire group to consolidate positions won during the 20th of November, while

patrols probed the line barring the advance to Saarburg, eight miles away.

In the meantime, while driving to Merzig, columns of the 10th Armored Division were stopped

by strong tank defense just inside Germany.

|

|

Along the Corps zone on the north, the Germans that build up formidable defenses over a period

of years. A typical tank defense consisted of several rows of heavy concrete "dragons teeth" behind

which a deep ditch was dug. The ditch was usually backed up by as many as 10 rows of steel stakes.

These defenses were accurately covered with heavy artillery and mortar fire, and, as a result, bridges

across the anti-tank ditches were destroyed as fast as they were completed.

It was revealed by prisoners taken in the area that the bridge at Merzig had been blown.

Realizing that the enemy was now aware of XX Corps effort to achieve a quick, surprise crossing at

Merzig, the Corps Commander directed the armor to consolidate positions and contain the area already

taken. He next dispatched another armored column and a regiment of infantry north to crack through the

switch line of fortifications of the Siegfried Line and reach to Saarburg.

After a heavy covering barrage, the armor jumped off on the morning of the 21st of November

and passed through Task Force Polk. The assault found the enemy ready and waiting with massed

artillery, cleverly camouflaged anti-tank positions, and intense automatic and mortar fire. The attack

was repulsed. On the next day, another attempt met a similar fate. The infantry was thrown into the

fight on November 24th, and, after two days of bitter fighting, managed to seize the town of Tettingen.

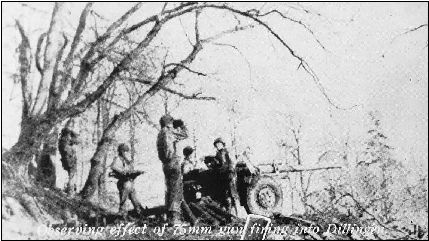

While this bitter but inconclusive action was going on in the north, the fall of Metz to XX Corps

freed more Corps forces for an eastward push. The Germans east of the city withdrew toward the Saar

and the security of the Siegfried line. Wishing to exploit the enemy collapse at Metz, General walker

ordered the 90th and 95th Divisions to seize a crossing over the Saar River between Dillingen and

Saarlautern.

|

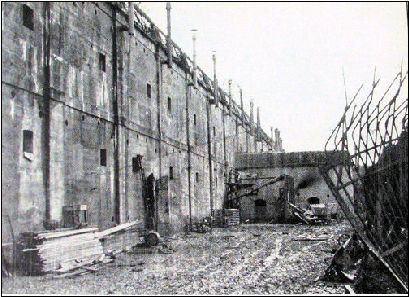

MAGINOT FORTS

Fortifications of the Maginot Line took terrific batterings

but in most cases were still useful.

The terrain approaching the Saar River is undulant, rolling in a series of gentle slopes to a high

plateau and then dropping sharply away to the Saar Basin. The area is laced by the French and German

Nieds and their minor tributaries, and each stream has carved out a well-defined valley. There are

wooded areas and dense forests of tall, straight evergreens, but most of the land is open and carefully

cultivated.

The road net was for the most part a poor one and the systematic blowing of the bridges and

culverts along the roads made matters worse. The situation was especially bad because almost all

movement of vehicles was canalized along the narrow roads.

The Maginot Line stood between the Saar and the Moselle. Situated on commanding ground,

these ponderous forts, although constructed by the eastward-minded French and now manned by a

westward-minded Germans, were still strong enough to serve as a barrier in the path of the XX Corps

offensive.

The Corps Commander decided to take the most direct route through the enemy held territory

between the Moselle and Saar, and ordered the 90th Division into an assembly area near the Nied River

on the 24th of November. Movement of the Division eastward from the assembly area was slowed by

roadblocks, mines, and blown bridges, but by nightfall of the same day some infantry troops had entered

Germany and were approaching the Saar. Observation posts were set up overlooking the river.

The 95th Division pushed on to Niedervisse and Denting where a hospital filled with over 1,300

seriously ill Russian prisoners of war was captured. As the advance continued on the 29th of November,

the enemy resisted stubbornly and fought savagely for every foot of ground. Resistance became

particularly bitter on the high plateau that looks down on Saarlautern in the Valley of the Saar and on the

Siegfried defenses beyond. Heavy artillery fire from east of the river and counterattacks, spearheaded

by tanks of the 21st Panzer Division, made the going slow and costly. One German division facing the

|

|

hard-pressed troops of XX Corps was called the "Twilight of the Gods" Division, indicative of the "last-

ditch" resistance put up by the German defenders west of the Saar. Now, the 95th Division became

involved in some of the heaviest fighting of its entire combat history. Many battalions were reduced to

50% of battle strength.

The 95th Division carried the Corps hopes for a bridgehead across the Saar and continued to

push on aggressively. It often attacked in darkness and in fog to overrun the German trenches and built-

up positions quickly before the startled defenders realized their danger. Hargarten, Merton,

Oberfelsberg, Alt-Forweiler, Falck, and St Barbara fell before the assault and bitter, costly fighting. At

times, the lines swayed back and forth along the high ridge before the Saar, as the Germans threw in

precious reserves of tank-infantry teams in a desperate attempt to halt the troops of the XX Corps west

of the river on the approaches to the Siegfried line.

The reason for this became apparent when the high ground was finally secured on December 1st.

Only a few miles of flat country dipped down to the river banks, and the Germans were forced to fall

back to the city of Saarlautern or east of the river to the high ground beyond. All hope of stopping the

advance of XX Corps to the line of the Saar was now gone.

These positions on the crest of the plateau were held as a safety limit on December 1st and 2nd

when 10 groups of aircraft, numbering over 400 bombers of the XIX Tactical Air Command, rocked the

enemy on both sides of the river.

The final obstacle west of the river was the town of Rehlingen where a thick belt of mines of

every type had been sown completely around the town. Engineer efforts to clear a path were repulsed

by accurate flat trajectory fire from east of the river and the engineers were methodically picked off.

Under cover of darkness and the supporting fires of Corps artillery, a gap was cleared through the mines

and Rehlingen was occupied.

The 90th Division, on the left flank of the 95th, pushed its way against tenacious resistance to the

west bank of the river and prepared to support a crossing with the fire of all weapons. Several groups of

Corps artillery moved into position, ready to lay down a curtain of steel in close support of the

operation.

At this time the 95th Division's right flank was exposed by the continued advance of XII Corps

to its river line further east. The Division was unable to advance further without bridging the Saar and

was attempting to do just that. Incapable of expanding its own troops to cover this area which was

heavily wooded and occupied by a large force of Germans, it requested aid from XX Corps

Headquarters.

The 5th Division, still investing the holdout forts at Metz, detached one of its regimental combat

teams. Attached to the 95th Division on the 1st of December this Task Force (Bell) had the immediate

objective of clearing Foret de la Houve. Also attached to the 95th Division at this time were the 6th

Cavalry Group and the 5th Ranger Battalion. On the 2nd of December when the woods were cleared,

another unit of battalion size from Metz arrived at St Avold.

The Corps was ready by the 2nd of December for its next mission: to seize Saarlautern and its

vital bridge across the Saar.

|

|

During the afternoon of December the 2nd, the Germans unleashed the first of the tremendous

artillery barrages that were to make the town of Saarlautern and the crossing site all but untenable for

weeks to come.

The assault waves drove into Saarlautern under this heavy fire and fought in the streets and

buildings of the town. The enemy defenses were designed with great ingenuity. Massive pillboxes and

bunkers were sandwiched in between normal dwellings and covered the neighboring streets with fire. A

harmless looking "Bierstube", a store, or even a doctor's residence might develop into a death trap with

thick concrete walls housing small determined bands of German troops.

Battalion objectives, at times, were a block of houses or even a single building. The town itself

had been converted into a fortress, and even peaceful looking parks became fiercely contested "no-man's

lands". Every street was a battleground echoing with the clatter of machine guns and the roar of tank

guns blasting in the heavy walls of reinforced houses. When night fell, the enemy could be heard

moving about in the streets and houses, but in the darkness and rain could not be accurately located.

It was realized that the fight through the town from house to house in a conventional type of

attack and to seize and hang on to the necessary bridgehead across the Saar would be too costly a

process for the already weakened troops. It was also likely that Germans would destroy the bridge as

the troops of XX Corps drove closer. So the 95th Division, with Corps approval, decided on one of the

slickest tricks of the war. Estimating the psychology of the German defenders, who fought skillfully,

but rigidly by the book, it was decided that the only feasible way of seizing the bridge intact was to

strike from an unexpected quarter.

After quietly patrolling the riverbank north of the town during the night of December the 3rd,

troops of the 95th Division paddled silently across the river in assault boats on the morning of the 4th at

0545 hours. By 0600 hours an entire battalion had crossed over without alerting the Germans and

started down the east side of the river. The route led over open terrain but the Germans, taken

completely by surprise, had left the outpost positions undefended. As the at battalion moved forward,

groups of the enemy coming to occupy the outposts were quickly and quietly captured. As the bridge

was reached, an armored scout car with a powerful radio was seized in a commando-like raid and its

occupants either bayoneted or captured before they could flash a warning.

The first shots of the whole operation were fired when the startled bridge guards attempted to

reach the switches and blow the bridge. One sentry was dropped 5 feet short of his goal.

As this amazing action was taking place, a task force of infantry and engineers bypassed centers

of resistance in Saarlautern and fought its way through the town to seize the other end of the bridge on

the west bank.

All wires leading to the bridge were immediately cut, and engineers began the work of clearing

the demolitions and mines from the structure. Four 500-pound American aerial bombs laid end to end in

the center the span, were discovered. These were disarmed and hauled off the bridge.

The bridge was a narrow life-line for large German forces west of the river and a pathway across

the Saar for the men and the guns of the "Ghost" Corps. The German forces east of Saar were slow to

react to the daring maneuver of the XX Corps troops in taking the bridge, but within a few hours they

struck hard in a frantic effort to retrieve their loss. Heavy guns and mortars from the high ground east of

the river poured a mass of shells on the bridge and in its vicinity. Guns of caliber as large as 240 mm

|

|

were used and the shelling became as heavy as any delivered by the German Army during the entire war

in Europe.

The XX Corps rushed troop reinforcements, tanks, and tank destroyers across to strengthen the

tiny foothold against strong counterattacks spearheaded by heavy tanks. The small bridgehead was

maintained and the order was to hold at all costs.

During the next several days, these strong enemy efforts to recapture the bridge went on. At one

time, a tank loaded with explosives and surrounded with suicide troops raced towards the bridge in a

desperate attempt to blow it up the tank. The tank was knocked out by a direct hit from a tank destroyer

only a few hundred yards from its goal. The bridgehead expanded, but slowly, against a stubborn,

persistent resistance. A view city blocks of Fraulautern and several pillboxes were cleared and held by

the infantry.

When the heavy concentrations laid on the bridge area from the Siegfried line slackened to some

extent, the engineers made a more detailed examination of the bridge itself and found that large-scale

preparations had been made for its complete destruction. The importance attached to the heavy stone

structure by the German commanders, and their fear of a crossing by XX Corps was clearly revealed

when eight huge chambers 25 foot in depth, filled with TNT, were found to be built into the peers of the

bridge and carefully camouflaged as manhole covers. Over 6,000 pounds of explosives were removed.

The XX Corps now held firmly in its grasp a huge stone bridge over the Saar River capable of

withstanding the heaviest pounding of German artillery. Over it poured more of the powerful battle

teams of the Corps. From the bridgehead, XX Corps was in a position to carve a substantial segment out

of the menacing Seigfried Line, and to carry on its mission of wresting from the Germans the rich,

industrial region of the Saar.

By the 6th of December, XX Corps had two more bridgeheads across the Saar, one by the 95th

Division about 2,000 yards to the south of Ensdorf and the other in the 90th Division zone at Dillingen.

Neither of these bridgeheads was able to push through the heavy defenses of the Seigfried Line.

Pillboxes and entrenchments were profuse. There were 40 forts in one area of 1,000 square yards. The

belt, itself, was approximately three miles in depth including antitank obstacles on the forward edge.

And in the XX Corps zone there was a second line of greater depth 10 or 15 miles to the rear.

These were obvious reasons for the slow and painful expansion of the bridgeheads at this point.

The enemy artillery was accurate and for days no bridges could be completed. As a result no heavy

weapons or armor were used. On the 8th of December the Saar had risen 2 feet, restricting even more

that trickles of food and ammunition into the bridgeheads. The cold and damp of winter were soaking

into the bones of the soldiers, some of whom in these areas had to be carried to their weapons. P-47s

flew in the low ominous clouds of fog to drop medical supplies. There were no tactical missions.

Such was the front line situation early in December as the remnants of the once mighty fortress

system of Metz surrendered.

With most of the 5th Division still containing the forts there was little choice for the Germans

but to starve or get out. Various attempts at reconciling the Germans were rebuffed but on the 6th of

December Fort San Quentin finally surrendered. There were 22 officers, 635 enlisted men, and two

American soldiers held as prisoners. All were ravenous. The same day the 87th Division supplied relief

in this area and a 5th Division battalion motor-marched to Lauterbach to rejoin his regiment there.

|

|

At 1200 hours on the 7th of December, unconditional terms of surrender were agreed upon and

Fort Plappeville was vacated. Again units in the 5th Division were relieved and on the 8th of December

proceeded by motor to Creutzwald. On this day across the Moselle River, Fort Driant, the next-to-last if

not the mightiest of all the forts, was surrendered. At 1600 hrs, with a single company remaining to

evacuate the prisoners, the remainder of the 5th Division prepared to move immediately forward to

within striking distance of the Seigfried Line.

Fort Jeanne D'Arc surrendered on the 13th of December to the 26th Division which moved in to

Metz for arrest.

When the 2nd Infantry Regiment closed in its area on the 9 th of December the 5th Division was

once again an integrated unit. The balance of the Division had progressed through many square miles of

woods heavily barricaded with roadblocks, craters, fallen trees, and antitank ditches.

With Ludweiler, Wadgassen, Hostenbach, and Differten cleared, the Saar River line in this area

was under control. With the link-up of the 10th Infantry Regiment and the 95th Division the entire

Corps zone now fronted the river.

Troops of the 5th Division from December the 9th to 19th practiced formations for assaulting

pillboxes, brushed up on demolition tactics, and maintained heavy patrols on constant watch for enemy

activity. Thus it was when the Germans mounted a furious, lashing counteroffensive in the Ardennes.

Combat Command "A" of the 10th Armored Division had the mission of capturing a bridgehead

at Merzig. In the days prior to the 6th of December this Command had come into contact with the

heavily defended fortifications of the Siegfried switch line and, with the 3rd Cavalry Group, was

restricted to probing along the trace from west to east. On the 6th of December control of the entire

north flank of the Corps was placed in the hands of the Cavalry Group. The Group's zone extended

from Besch on the Moselle River to Schwemlingen with a patrol reaching Driesbach. It was operating

on a 15-mile line, nearly a third of the Corps front.

In retrospect the successful conclusion of the battle for Metz was the result of the close

teamwork and loyal strenuous efforts of every member of XX Corps and attached troops. The breaching

of the Moselle and the encirclement of the entire fortified region of Metz was a military operation that

required the intensive employment of almost every branch of the service. And important in the

operation were all Corpsmen from the man with the M1 on the front lines to the man in the chemical

battalions which generated smoke to screen Corps activities from enemy eyes.

The guns of the Corps artillery battalions were frequently emplaced within range of small arms

fire. This was necessary in order to give the closest possible fire support to the hard-pressed Corps

assault waves which were battling against some of the strongest fortifications encountered anywhere in

World War II. Instances were noted of 8-inch guns firing from ranges of 1,000 yards in an effort to

drive the enemy from his concrete bunkers.

The steel steeds of the 735th Tank Battalion and tank destroyers of the 4th Destroyer Group

roared up to the very walls of the forts to rip gaps in the embrasures for the infantry.

The engineers of XX Corps conducted their bridging operations in mud and cold, under heavy

shelling, to speed the build-up of the offensive. Then they moved in with the infantry to blast their way

into forts with satchel charges and "beehives".

|

|

The 69th Signal Battalion, the "nerve system" of the Corps, kept the "brain" or Corps

Headquarters in constant contact with the encircling "arms" of the Corps units which were engaged in

choking off the fortified region of Metz. The wearers of the crossed flags had a rough job in repairing

wire knocked out by enemy artillery and in moving all over the Corps area in all kinds of weather with

scattered enemy groups harassing them.

The 819th Military Police Company and the various intelligence agencies made invaluable

contribution to the Corps effort in directing the heavy civilian population.

The numerous medical corps units, from the man with the Red Crosses on his helmet to the huge

field hospitals, were a smoothly functioning, mercy team. They were always there to relieve the

suffering and reduce the number of deaths from battle wounds and exposure.

The tiny, defenseless liaison planes were a familiar sight over the front lines, pinpointing enemy

gun batteries and strong points, and often coming to the rescue of isolated units with badly needed

supplies.

The battle for Metz was an operation on Corps level and its successful completion remains a

lasting tribute to a great fighting Corps.

Successful completion of a campaign had its aftermath of ceremonies and formations. This was

a great climax to the years of preparation by the XX Corps. The liberation of the historic city of Metz

brought further honors to the Corps, which already carried the famed battle streamers of Verdun,

Chateau-Thierry, and the Marne.

On the 29th of November, the French Government bestowed high tribute on General Walker

when he was made a member of the Legion of Honor, Officer Class at a great civic ceremony staged in

Metz.

At the same time, General Collier and Brigadier General Julius E. Slack, XX Corps Artillery

Commander, received the Legion of Honor, Knight Class.

Major General Andre Dody, Military Governor of Metz, made the awards in the Place de

Republique where thousands of people had gathered to witness the proceedings and cheer the parading

troops of France and the United States. These were the first American troops to be so honored by the

French Government.

Massed standards and banners of XX Corps divisions and regiments headed the big parade and

review, which was taken by General Walker. French and American military bands provided the music,

and the rumble of artillery fire in the distance provided additional sound effects.

Front line troops of XX Corps who participated in the capture of Metz were heartily applauded

by the populace. French Regular Army troops who took part in the parade made a fine showing.

After the general officers had received their decorations, the award of the Croix de Guerre with

Palm was made to Colonel Charles G. Meehan, Captain David W. Allard, Sgt. S. Bornstein, Captain

Guy de la Vasselais, Lt. Col. J. W. Libcke, and Colonel H. R. Snyder received the Croix de Guerre with

|

|

Gold Star, Lt. Jacque Desgranges was the given Croix de Guerre with Silver Star, and the same

decoration with Bronze Star went to T/Sgt., Donald Post, T/4 Denver Grigsby and T/4 H. J. Schonhoff.

The demonstration at Metz took place a week after General Walker officially turned the city over

to the French, following its capture by infantry and armored divisions in two weeks of hard and bloody

fighting. Hailed by the press of Metz as the "Conqueror of Metz", General Walker was warmly received

by the people of the liberated city.

At a formation held the next day at Corps Headquarters, General Collier made further awards to

officers and men of the XX Corps.

The Croix de Guerre with Palm went to Colonels R. John West, Henry M. Zeller, Joseph

Shelton, Chester A. Carlsten, and William B. Leitch. Receiving the Croix de Guerre with Gold Star

were Colonel William H. Greene, Lt. Col. Melville I. Stark, Lt. Col. Joseph Cowhey, Lt. Col. Napoleon

A. Racicot, M/Sgt. John Taylor, and M/Sgt. Van K. Barre. The Croix de Guerre with Bronze Star was

given to First Sgt. Alexander Berg, T/Sgt. Roy S. Hahn, and T/4 Clarence La Pierre.

THE SAAR-MOSELLE TRIANGLE

DOORWAY TO TRIER

Fighting east of the Saar River had developed into a bitter slugging match against tenacious

enemy resistance. In the towns of Saarlautern, Fraulautern, Saarlautern Roden, Ensdorf, and Dillingen,

each block became a separate battlefield as tanks roamed up and down the streets looking for targets.

Enemy machine guns were zeroed down every thoroughfare. To gain ground, Corps infantry resorted to

the technique of "mouse-holing", blasting their way through reinforced concrete walls from house-to-

house. They cleared the houses room-by-home only to have the Germans infiltrate back again.

Scattered through the towns and around the surrounding countryside was an almost impenetrable

maze of pillboxes. They were usually dug in flush with the ground with only the turret exposed. In

addition, they were carefully camouflaged with natural growth, and were hard to locate even from the

air. Even when detected, the heavier types were a problem to reduce. Artillery, alone, was rarely

sufficient. One steel turret, encountered during the fighting at Ensdorf, withstood several direct hits

from a 155 mm self-propelled gun and over 50 rounds of 90 mm fire from a tank destroyer. The

pillboxes were placed so as to support each other and lay down a continuous band of fire along all likely

approaches. When Corps assault teams fought their way close to these defenses, the Germans retired

inside and called down their own artillery on the positions.

Calls for the close support of Corps artillery were frequent and the fire-happy "red-legs" were

never too cold nor tired to respond to the call of "Fire Mission"!

|

Many unequal duels were fought at close range between German guns, well protected by several

feet of concrete, and the heavy cannon of Corps artillery, dug into the deep Lorraine mud behind the

doubtful protection of sandbags. On one day alone, over 18,000 rounds were fired against the Germans

by Corps artillery units. German prisoners expressed wonder at Corps "automatic" artillery though

ammunition was restricted and firing was limited accordingly.

When the German defenders were driven deep into their shelters by heavy bombardment, the

infantry-engineer assault teams drove in with small arms fire, fragmentation grenades, and explosive

charges to clear the pillboxes of the enemy. After their capture, the concrete walls of the enemy

defenses were usually destroyed by about 1,000 pounds of TNT.

Other factors besides the fierce enemy resistance made the going rugged. The weather was cold

with light snow and almost continual rain. Foxholes filled with water so fast that they were almost

useless. Another "war of nerves" developed because of the Wehrmacht's ingenious and extensive use of

mines and booby traps. In abandoning buildings, the Germans often planted large and carefully

concealed time bombs which, in some cases, resulted in casualties for units seeking billets as protection

against the miserable weather.

The Wehrmacht troops lashed back with strong, tank-supported counterattacks but gradually the

bridgeheads were developed and held. A breach had been ripped in the first line of defense of the

Siegfried Line itself.

LIBERATION DAY: THIONVILLE

The 12th of December 1944 was Liberation Day at Thionville. It was a joyous day to people

who after five years were again under their own rule and were again beginning to enjoy their own way

of life. They did not now have Nazi appointed officials, but those of their own choice. On Liberation

Day, children wearing colorful native costumes of the countryside danced happily about. Civic clubs

and organizations paraded with their banners streaming. Blue uniformed Chasseurs with feathered

berets and gleaming French horns added to the festive air. Officers and unlisted men from XX Corps

|

|

represented the liberating army and were most hospitably received at the City Hall. The Book of Honor

was signed and then there was a public reception at which many a XX Corps soldier sampled Moselle

wine.

In the meantime, Third Army and XX Corps were planning a drive to and over the Rhine and the

seizure of Frankfurt. XX Corps Field Order No. 14 dated December the 16th called for a continued

advance to the east to penetrate the Siegfried Line. Two Divisions launched the attack on the 18th of

December. The 5th Division, replacing the 95th Division at Saarlautern, inched its way past pillboxes

and concreted resistance. At Dillingen, the 90th Division used its own bridgehead and until the 20th of

December seemed on the verge of consolidating this area.

The Nazi High Command on the Western front had, however, made some plans of its own. On

the 16th of December, the great German counteroffensive had begun in the Ardennes.

The Third Army was compelled to discontinue its aggressive attacks to the east and to swing the

biggest part of its forces to the north. The XX Corps took up a defensive position along the line of the

Saar. The hard-won bridgeheads at Dillingen and Ensdorf were abandoned; but the bridge at Saarlautern

was held again by the 95th Division and remained both a constant threat to the Germans and a painful

reminder of how they had been outwitted in early December.

On the 17th and 20th of December, respectively, the 10th Armored Division and the 5th Infantry

Division were hurried north to knife into the southern flank of the German bulge, and so these divisions

passed from the control on XX Corps. The Corps continued, however, to hold its zone along the Saar,

and it made preparations in depth to repulse a possible German offensive in its sector. The Corps also

kept up its policy of making repeated aggressive feints to keep the enemy off balance and in fear of an

all-out attack, thus preventing the shift of German reserves to the "Battle of the Bulge". Limited

objective attacks and aggressive patrolling were the main activities of the thinly spread XX Corps during

the remaining days of December and the entire month of January.

On the 23rd of December 1944, the city of Metz held civic ceremonies honoring the heroic XX

Corps, as citizens of the city gathered to celebrate their return to freedom after five years of German

occupation. Children in native costumes joyously unlivened the streets of the city. Troops of the newly

organized a French Army as well as the veteran combat units of the vaunted XX Corps participated in

the review.

A special commemorative medal was struck for the colors, and a special battle streamer prepared

in the colors of the Citadel of Metz. The latter was attached to the XX Corps flag beside its other

streamers, each significant of a great achievement. In this square near the Cathedral of Metz, General

Walker, representing the officers and soldiers of his Corps, was made and "Honorary Citizens of the

City of Metz" when he was presented with a handsomely embossed scroll, indicating such citizenship.

General Walker, accompanied by a combat soldier of the Corps, presented the city with a framed

and decorated map showing the route of the XX Corps in its rapid advance across France resulting in the

liberation of Lorraine.

The Ardennes offensive had started six days earlier and the extent of the penetration was still

unknown to the citizens of Metz, who became fearful. However, the mere presence of the Corps

Commander for a few minutes serve to reassure them that Metz would not be given up.

|

|

On the 31st of December, the 160th Cavalry Group on the left flank of XV Corps to the south

had warning that an attack would be made on its left. The implications were that a penetration might be

effected between the XV and XX Corps. The 95th Division thus alerted followed developments closely.

On the request of the 106th Cavalry Group to Division Headquarters, the 5th Rangers was notified to be

prepared for instant movement. Later the entire 378th Infantry Regiment which was in Division Reserve

received warning orders. It was reported that the enemy had an estimated 2,000 troops with ample

artillery support. By this time the right flank of the 95th Division was exposed and penetration was

noted toward the rear.

Although the 106th Cavalry Group did not have the information nor the whereabouts of the

enemy, subsequent action by the 2nd Battalion, 387th Infantry Regiment, located and engaged

approximately 300 enemy troops in the town of Werbeln and unknown dispositions in Schaffhausen.

Both towns were cleared by the 2nd of January in better house-to-house fighting. The Cavalry Group

then took over the sector and the 95th Division returned to a normal defensive routine. This attack

seemed to be part of an over-all New Year's demonstration for Hitler in which all units in Germany were

to participate.

According to captured German prisoners, if these preliminary piecemeal attacks had been

successful, a drive approaching division size would have been made. Quick response by the 95th

Division had saved any undue action.

Passive defense was maintained from the 3rd to the 20th of January. It employed the use of

nightly reconnaissance patrols and attempted to keep the enemy guessing at feinted moves.

Captured prisoners of war in the Saarlautern bridgehead and an increase in patrol activity now

gave evidence that an attack might be expected soon. On the night of the 19th of January new prisoners

revealed that the attack would come before dawn.

Patrols began to infiltrate skillfully at 0500 hours so that surveillance of the enemy could be

maintained for the flushing-out to come with daylight.

Beginning at 0600 hrs and continuing until early afternoon, intense enemy artillery fire covered

the area. Following the initial barrage, troops were seen to move into the open streets and openly

advance toward XX Corps lines. Some moved out too soon and were caught in their own shelling. The

action of the attackers, exclusive of the patrols, was inept and prisoners were found who did not even

know their own companies. The whole attack lasted less than one hour and yet it indicated a changing

complexion of the German defenses.

Our patrols were also in action across the river and were keeping the Germans apprehensive.

This was the situation on the 28th of January when the 26th Division relieved and 95th Division for a

move north to Belgium.

The growing weight of the Third Army attacks against the Ardennes salient cost XX Corps the

loss of another veteran division when the 90th Division left Corps controlled to move north. The 94th

Division was moved into the Corps zone to occupy positions along the north flank. To give this untried

Division battle experience, XX Corps committed it to a series of limited-objective attacks against the

base of the Saar-Moselle Triangle.

|