90TH

DIVISION ENTERS LINE OCTOBER 21-22

THE policy of the 1st Army during

this offensive was to use every division to its maximum capacity. The number of combatant divisions was

limited, and the United States army had been given a task, the achieving of

which virtually meant the defeat of the German armies on the Western

front. All the Allies were putting in

every ounce of energy at this time in the hope of ending the war before winter. Hence it was necessary that the division, which

is the principal unit of combat, should so conserve its force as to be able to

carry on a long sustained operation under trying circumstances. With this in view, the policy was followed

of designating one brigade as an attacking brigade and the other brigade as the

reserve brigade. The attacking brigade

was thus replaced by the reserve one when heavy casualties and utter exhaustion

made it absolutely necessary that the former be withdrawn for rest and

replacements.

So when the 90th Division went into

the line of the Meuse-Argonne front, the night of October 21-22, the 179th

Brigade relieved the 10th Brigade of the 5th Division (the 357th took over from

the 6th Infantry, and the 358th from the 11th Infantry) , and the 180th Brigade

moved up from Jouy and Rampont to the Bois de Cuisy. The 155th Field Artillery Brigade (80th Division), which was

already in the sector, was attached to the Division.

The artillery fire was very severe

the night of the relief, and not all of the machine guns had been cleared out

of Clairs ChLne woods.

Lieutenant Thomas R. Ridley, Company L, 358th Infantry, was killed the

morning of October 22 by high explosive in the Bois des Rappes.

Where the 5th Division had left off

the 90th Division took up the task of developing the Freya Stellung and

establishing a good jump-off position for the next general attack, which came

on November 1.

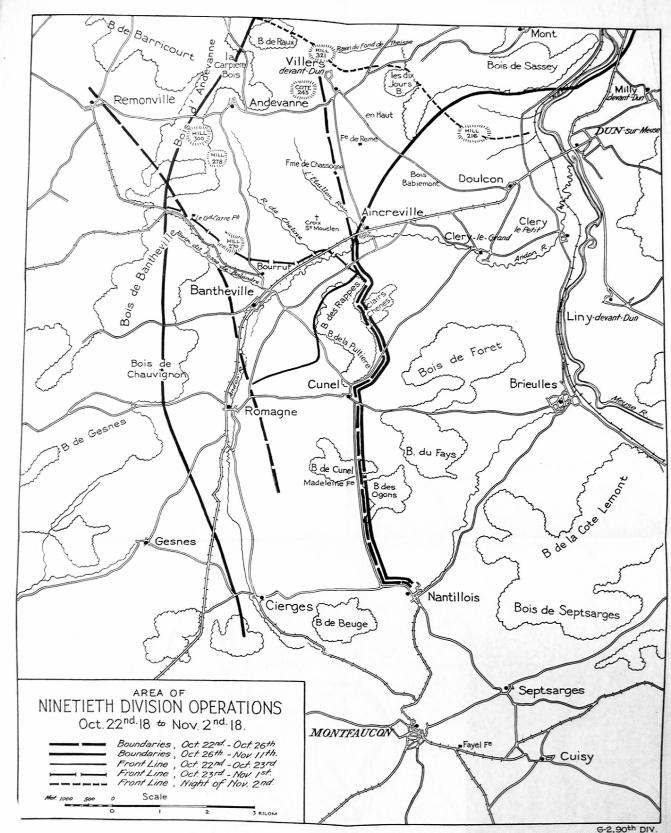

The front line, as taken over on

October 21, ran as follows: The 357th Infantry connected with the 89th Division

on the northern outskirts of Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, and held a line extending

over the ridge northwest of the town to the Bois de la Pultiere, whence the

358th Infantry extended the line around the western and northern edges of the

Bois des Rappes to the northeastern corner of the woods, there making

connection with the 3d Division. The

89th Division remained on our left until the armistice. The 3d Division was relieved on the night of

October 26-27 by the 5th Division, which retained thereafter the position on

our right.

Thus it will be seen that the

Germans held a pocket between the Bois des Rappes and Bois de Bantheville, in

which were included the towns of Bantheville and Bourrut. The first mission of the 90th Division was

to straighten out the line by cutting off this pocket.

About nine o’clock on the night of October 22, a long message in

code was received at P. C. O’Neil – a deep German dugout at Madeleine Farm –

which message, when translated into every-day language, was an order to advance

the line on the following day to include the towns of Bantheville and Bourrut

and also the ridge to the northwest of Bourrut, known as Hill 270.

View of village of Bantheville, showing the results of

heavy shelling,

first by American artillery and later by the Germans.

THE TAKING OF BANTHEVILLE AND HILL 270

THE mission assigned the 179th

Brigade was achieved by the 1st and 3d Battalions of the 357th Infantry. To the 1st Battalion was assigned the

principal role. The commanding officer,

Major Aubrey G. Alexander, received his orders at the brigade P. C. after

midnight of October 22-23, and rushed back to his own P. C. to move his

battalion under cover of darkness to their jumping-off place in the Bois de

Chauvignon, a kilometer and a half southwest of Bantheville, in the sector of

the 89th Division. By starting from

this position it was hoped to avoid the losses which a long advance across the

open north of Romagne would naturally involve.

From this position the 1st Battalion was to advance, first due north,

cleaning out the sunken roads which ran into Bantheville from the west, and

also the enemy machine gunners who were still believed to be lurking in the

Bois de Bantheville. Having reached the

sunken road, Company D was to veer to the right, mopping up Bantheville, then

turning again to the left to take Hill 270 in flank. The 3d Battalion was to jump off from its trenches and advance

north, taking Bourrut and connecting with the 3d Battalion of the 358th Infantry.

The affair started at 3 P. M., after

thirty minutes’ artillery bombardment of Bantheville and Bourrut. Bantheville was soon taken, together with a

machine gun and the crew left to delay the American advance. But on leaving the town, Company D was

forced to pass through a heavy barrage.

Undaunted, they made their way through the curtain of fire, turned aside

to clean up some machine gun nests in Bourrut which were holding up the 3d

Battalion, and reached the objective.

Captain Beauford H. Jester had been badly gassed during the attack, but

remained with the company.

The total casualties from this

affair were only about twenty. The 3d

Battalion suffered the heaviest.

Captain Harry E. Windebank was killed by shell fire: Lieutenant C. W. Paine,

Company I, was knocked down and slightly injured by high explosive; and

Lieutenant E. C. Martin, Company I, was saved only by his helmet, a fragment

piercing the steel and entering his head.

The regimental 37-mm, platoon was

able to render valuable assistance in this attack by firing on machine gun

emplacements. The trench mortar platoon

followed up the infantry, and remained to consolidate the position. Its commanding officer, Lieutenant Robert C.

Murphy, was wounded by high explosive on October 26 and died two days later.

Lieutenant Albert Garther, Company

A, who had joined the regiment at Bois de Sivry, was killed by a machine gun

bullet. He had received his commission

at an Officers’ Training School in France.

The success of the 179th Brigade in

establishing its position, and in sticking to it without a single man wavering

or yielding an inch (this success coming at a period of the operations of the

1st Army when straggling had become a curse), won the highest commendation of

the higher commanders. The commanding

general of the army sent the following congratulations:

“The army commander directs that you

convey to the commanding general, officers, and men of the 90th Division his

appreciation of their persistent and successful efforts in improving the line

by driving the enemy from the Grand Carré Farm and the Bois de Bantheville.

(Signed)

H. A. DRUM.”

To this message the commanding

general of the 3d Army Corps added the following:

“The difficulties under which the 3d

Corps has labored to improve its position have been numerous and great, and the

part the 90th Division took in establishing the present advantageous position

of this corps is deeply appreciated by the corps commander, and he adds his

congratulations to those of the commanding general of the army for the vigorous

and untiring efforts of the personnel thereof, whose resolution and fortitude

are worthy of the best traditions of the American.

(Signed)

J. L. HINES.”

That night word came down from corps

headquarters that intelligence reports pointed to an enemy withdrawal for ten

miles opposite our front, and orders were given to gain and keep active contact

with the enemy. Patrols from the 357th

Infantry soon gained contact of the liveliest sort and were forced to retire to

our lines. Lieutenant Bateman of

Company I was taken prisoner. Two

companies of the 3d Battalion, 358th Infantry, succeeded in crossing the Andon

brook before being halted by machine gun fire along the Aincreville-Bantheville

road. Major Terry D. Allen, commanding

the 3d Battalion, was cited in a division order for his coolness and bravery in

this action.

At 11 o’clock on October 24,

following an artillery preparation, a further attack was made to mop up

positions from which the enemy continued to harass us. The result was that the top of Hill 270 was

established as No Man’s Land. During

the brief struggle the 1st Battalion alone took forty-one prisoners and six

machine guns. But the 1st Battalion

also suffered heavy losses, particularly in the fighting around Grand Carré

Farm. Companies E, G, and H, 2nd

Battalion, which had been sent up to reinforce the 1st Battalion, also

participated in the successes and losses.

Lieutenant Henry C. DeGrummond, Company K, and Lieutenant Edmund K.

Whitaker, Machine Gun Company, 357th Infantry, received machine gun

wounds. Lieutenant Whitaker was wounded

while making a reconnaissance for his guns to protect the 1st Battalion’s right

flank. Corporal Charles F. Chaffin

continued his work and carried out his orders.

Lieutenant DeGrummond was wounded before the advance got under way.

The Germans retaliated during the

afternoon with a mustard gas concentration.

Captain William F. Cooper, commanding the 3d Battalion; Lieutenant Ed.

McCoy, his adjutant; and Captain Joseph M. Simpson, 357th Machine Gun Company,

were evacuated. Lieutenant W. B.

Johnson, regimental intelligence officer, took command of the battalion for a

day, until relieved by Captain John Hopkins, Headquarters Company.

During the day of October 25

occurred an incident both dramatic and amusing in its appeal to the human

emotions. Aniello Spamanato, an Italian

who had been drafted and was now a private in Company L, 357th Infantry, found

himself, with three other soldiers, on outpost duty just north of Bourrut.

Their position was being harassed by a machine gun manned by six

Germans. After killing one German with

a rifle shot, Spamanato suggested to his comrades that they go after the

machine gun. The others being

unwilling, the little Italian started out alone. He killed two of the Germans and captured the remaining three,

whom he forced to carry the gun back to our lines. He was allowed to conduct his prisoners back to division

headquarters, and there, in broken English, Spamanato explained what he had

done. For this exploit he was awarded

the D. S. C.

GERMAN

COUNTER-ATTACK

THE following days were severe

and trying. About 5:30 P. M., October

25, the Germans made an attempt to regain their lost ground. Following a terrific preparation lasting

about forty minutes, enemy infantry made a rush for the top of the hill

opposite Company D, 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry. The counter-attack was stopped by rifle and machine gun

fire. The 357th Machine Gun Company,

which had played its part in taking these positions, rendered very great

service by holding them and continually harassing the opposing forces.

The official communiqué for October

26 read: “On the Verdun front, yesterday evening, the enemy extended to the

west side of the Meuse his efforts to wrest from our troops the gains of the

preceding days. In the region of

Bantheville, after artillery preparation lasting half an hour, he attacked our

positions between the Bois des Rappes and the Bois de Bantheville. After sharp fighting he was repulsed with

heavy losses, our line remaining everywhere unchanged.”

On the afternoon of October 26 the

second counter-attack was delivered.

This was noted in the official communiqué of October 27 as follows:

“North of Verdun the enemy renewed without success his attempts to regain the

ground lost in recent fighting.

Yesterday evening an attack launched with strong forces against our

positions between Bantheville and the Bois des Rappes broke down under our

artillery fire before reaching our lines.” A modest notice, but full of

suggestion! It is safe to assume that

no Texan or Oklahoman, on reading the communiqué for October 27, realized that

lives of loved ones had been in the balance, but that the danger “broke down.” So close was the fighting that hand-grenades

were used.

For a week the 3d Battalion, 358th

Infantry, clung perilously to its position along the Aincreville-Bantheville

road. The two companies which held this

position were in a hotbed of Boche snipers and trench mortars, which found

effective concealment in Aincreville and the Ravin l’Etaillon. Early on the morning of October 23, while

patrolling toward Aincreville, Lieutenant Lyle K. Morgan, Company M, was killed

by a rifle shot, and immediately afterward George F. Dobbs of the same company

was severely wounded. Owing to the

peculiar situation of the 3d Battalion, the only avenue of communication was

down the open slope from the Bois des Rappes and across the Andon brook, and

the slightest move by day brought forth a hail of bullets from German

sharpshooters. “Chow details” which

attempted to fetch a bit of food for their comrades across the creek suffered

particularly until Sergeant Charles Ward, Company K, with deadly aim succeeded

in “bagging” the Hun. Sergeant Ward

himself received several bullet holes in his helmet and the back of his blouse.

The 344th Machine Gun Battalion,

commanded by Major Claude B. Gullette, played an important role during this

period. Its best opportunity came when

two companies in the Bois des Rappes succeeded in catching the Germans in a

terrific barrage while forming up in the Ravin Cheline for a counterattack

against our positions. The 358th

Machine Gun Company, commanded by Captain Mark D. Fowler, also participated in

this barrage. On October 30 the machine

guns of the 179th Brigade assisted the 5th Division in the taking of

Aincreville by firing on enemy positions to the north and west of the

town. Aincreville was easily taken, but

was immediately afterward subjected to such heavy artillery fire that it was

necessary to withdraw from the town.

Captain Clarke W. Clarke, who had brought the 358th Machine Gun Company

to France, was gassed at Vilcey-sur-Trey on September 14.

The stubbornness of the fighting in

this region is to be attributed not only to the determination to hold this

precious ground, but also to the quality of the German divisions opposing our

troops. When the Division entered the

line the sector opposite was held by the 123d Division, with which the men had

become acquainted in the St. Mihiel attack.

As has been seen, this division was in reserve at the beginning of

operations on September 12, and was thrown in to counter-attack, colliding with

the 3d Battalion, 357th Infantry, on September 14. All three of its regiments were identified by prisoners captured

in taking Bantheville. Following this

attack, however, two regiments were relieved by the 109th Body Grenadier

Regiment and the 110th Grenadier Regiment of the 28th Division, which were put

in by the enemy to regain the lost ground and hold it at all costs. On the night of October 26-27 the 40th

Fusilier Regiment of the 28th Division came into line between the 109th and the

110th, with orders to counter-attack on the morning of October 27.

This 28th Division was one of the

best divisions in the German army, and had won such a reputation as shock

troops that it was known as “The Kaiser’s Favorite.”

“Chow” detail, Company D, 358th Infantry, 90th

Division, taking bread

and hot “chow”

to the men I front lines, Bois des Rappes,

near Cunel,

Meuse, France, October 25, 1918.

REAR AREAS SHELLED

NOT only the troops actually in

the front line, but the rear areas as well, were subjected during this period

to intermittent bombardment which took its daily toll. The Bois des Rappes and the area around

Madeleine Farm were favorite targets.

The 1st Battalion, 358th Infantry, in support of the 3d Battalion,

suffered heavily from this fire.

Lieutenant (later Captain) J. P. Woods and Lieutenant Haley G.

Heavenhill were wounded by shrapnel; the woods continually reeked with “yellow

and blue cross” gas, and Lieutenant Ralph D. Walker, the sole remaining officer

of Company D, was overcome and evacuated.

On October 25, when the battalion was moving to the northern edge of the

Bois des Rappes to support the 3d Battalion more closely, a shell dropped

directly in front of Lieutenant Samson B. Brasher, Company A, killing him and

his orderly, Private James F. Matlock.

Nor was life still further to the

rear any more pleasant. The headquarters

of the 180th Brigade, in Nantillois, were continually shelled; Lieutenant John

H. Byrd, assistant adjutant being severely wounded by a shell fragment while

eating lunch. The

Montfaucon-Nantillois-Cunel road was constantly harassed, particularly in the vicinity

of the junction of the Nantillois-Cunel and the Nantillois-Cierges roads. There were ammunition and food dumps near

this junction. Field Hospital No. 360,

which was also in this neighborhood, suffered from the searching artillery fire

on October 25. A shell passed through

one ward tent and demolished two other ward tents. Two men were killed, a sergeant was mortally wounded, Lieutenant

Lee Woodward and twelve enlisted men were seriously wounded, and four other men

were slightly injured.

The 90th Division chaplains, with

the aid of details furnished by infantry and engineer units, undertook the work

of burying the scores of dead of the 4th and 5th Divisions. Which had suffered very heavily in the

severe fighting in this region. There

were corpses in all parts of the divisional sector, particularly in the Bois

des Rappes. The burials were carried on

despite the constant shelling. While

engaged in this duty, Chaplain Charles D. Priest was mortally wounded by the

explosion of a shell near him on October 27.

He was buried at Rampont on October 30 by the Division chaplain. Chaplains F. A. Magee, 357th Infantry, and

Milles F. Hoon, 358th Infantry, were wounded about the same time.

Chaplain Priest was known as one of

the bravest men of the Division, and was posthumously awarded the D. S. C. On one occasion he buried a man in a

position enfiladed by a German one-pounder.

After two burial squads had been driven from the work, Chaplain Priest

himself shouldered the tools and went out and dug the grave, placed the body in

its resting-place with a short service, covered it over, and returned to our

lines. The one-pounder dug holes in the

ground all around the chaplain but he stuck to his work.

Despite the severity of the fighting

which marked the establishing of our line north of Bantheville, the operations

were only a prelude to the general attack on the army front on November 1. The 180th Brigade was chosen to make this

attack for the Division.

All corps orders during this period

directed the Division to “improve its position in preparation for further

attack.” On October 28 was issued the

corps field order outlining the attack, big preparations for which were already

under way. By this time the 179th

Brigade was pretty well spent. Only

eight officers remained in the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry, and some

companies were so badly reduced that it was necessary to consolidate them. October 31 proved to be “D minus one day” –

that is, one day before the big attack.

The 180th Brigade, which was to

deliver the attack, was brought into line the night of October 30-31, long

enough before the attack to allow it to become familiar with the terrain. This policy proved to be doubly wise in view

of the heavy artillery reaction the night before the attack, which reaction

would have caught both brigades at the worst possible moment, when relieving

and relieved troops are both in the forward zone. As it turned out, the relief was made without a casualty.

On October 30 the Division P. C.

moved to Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, being housed in dugouts constructed by the

Engineers and made more comfortable by the Headquarters Troop under the

direction of Captain Donald Henderson.

The stage was now set for the third

and last phase of the battle of the Meuse-Argonne.

Former German headquarters building in Cunel,

used as dressing station be 3d Battalion, 359th

Infantry.

BRIGADDIER-GENERAL ULYSSES G. McALEXANDER, U.S.A.

Commanding the 180th Infantry Brigade

TEXAS BRIGADE BREAKS FREYA

STELLUNG

PRIOR to arriving at a decision as to the best manner of

attack, any commander, from a corporal leading a squad to General Pershing

himself, must study all the factors affecting his own and the enemy

forces. This mental process is

described in Field Service Regulations – the Bible of the soldier – as an

“estimate of the situation.” In order,

then, to understand the plan of attack of November 1 it will be necessary for

the reader to make such an estimate.

Under the head of our own forces, it suffices to say that when the 180th

Brigade jumped off on November 1 its strength was only at 50 per cent, of its

officers and 65 per cent of its enlisted personnel. The headings which will require explanation are: the terrain, the

organization of that terrain by the Germans for defense, and the intentions of

the enemy – that is, whether or not the Germans planned to hold their present

positions or were merely lighting a rear-guard action preparatory to a general

retirement.

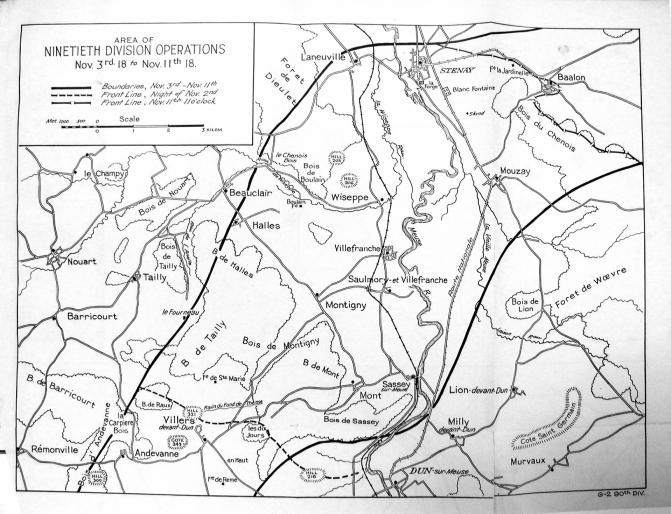

First, then, must be understood the

terrain over which the advance was to be made.

The principal feature on the immediate front of the Division was the

wooded ridge running north along the left boundary – that is, roughly speaking,

between Grand Carré Farm and the heights north of Andevanne. From this high ground there was an open

slope toward the Meuse. This open

ground was cut on the front of the 90th Division into three ridges, and by two

ravines which flowed in a southeasterly direction into the Andon brook. The highest point of the region was a

heavily wooded hill known as Côte 243, which was just west of

Villers-devant-Dun and linked up with the wooded ridge along the left boundary.

Sloping north from Côte 243 was a

relatively open space of an average width of two kilometers before entering the

dense Bois de TailIy, Bois de Montigny, Bois de Mont, and Bois de Sassey. The first two woods, which formed a

continuous forest, were separated from the last-named two woods by a deep

ravine, along which ran the Villers-Montigny road. The northeastern edge of this wooded area marked the crest of a

high bluff. From the foot of these

bluffs to the Meuse the country was flat and open.

As to the organization of the

terrain by the enemy, suffice it to say that on November 1 the 90th Division

held a line opposite the Freya Stellung.

This defensive position, which the Germans relied upon to hold the

American attacks, and was organized in depth to include a first or covering

position between Aincreville and Grand Carré Farm, and, secondly, the main line

of resistance, which embraced Andevanne, Côte243, and Villers-devant-Dun. And it was manned with troops rated among

the best in the German army. The enemy

order of battle, at the beginning of the operation, was, from west to east,

88th Division, 28th Division, and 107th Division. “The Kaiser’s Favorite” held most of the sector, but there were

elements of the 88th and 107th Divisions on the flanks.

As the operations in the

Meuse-Argonne region shaded into what is popularly known as “open warfare,” as

compared with “trench warfare” and “warfare of position,” there was not to be

found on this front the maze of trenches and entanglements, such as faced the

Division at St. Mihiel. The artificial

defenses consisted for the most part of pits for machine gunners and

“fox-holes,” The latter are individual pits dug at scattered intervals so as to

afford the maximum protection from shell fire.

There was some wire, particularly on Côte 243, but the enemy relied

principally upon machine guns, concealed in woods, holes, and isolated farms or

villages, to bar the way.

Practically all of the above

information was known by General McAlexander before he was called upon to make

his decision as to the manner in which the attack would be made. This information was supplied by the second

section of the General Staff. The story

of the life of the Boche, his home and his habits, had been pieced together by

Lieutenant-Colonel H. C. Tatum and the regimental and battalion intelligence

officers, from evidence received by ground observation, aerial observation and

photographs, the statements of prisoners, and other sources.

The one element in the “estimate of

the situation” still a bit doubtful was “intentions of the enemy.” Several

matters are worthy of note in this connection.

In the first place, it was evident that the enemy would hold on to every

inch of soil here in order not to sacrifice what remained of the big armies

still retreating from the Laon salient toward Germany, Then there was the

quality of the divisions opposing the 90th Division – first class; and the sort

of resistance they offered – to the death.

At the same time it was necessary to keep in mind the possibility of a

retirement or a break through at any time, and the American armies must be prepared

to take up the pursuit.

FIELD ORDER No. 13

THE plan of attack for the

Division, which was issued as Field Order No. 13 – lucky number! – was

generally as follows:

The 90th Division, as at St. Mihiel,

was on the right flank of the 1st Army attack.

On our left was the 5th Corps, which by a direct drive was to seize the

ridge of the Bois de Barricourt and the heights northeast of Bayonville, thus

effecting a complete rupture of the enemy’s main line of resistance the first

day. The 5th Division – the other front

line division of the 3d Corps – was to hold on our right, merely sending out

patrols to reconnoiter the Bois de Babiemont and Côte 261, the only two spots

of possible danger in their front.

These two points were on the brink of a huge basin, in the center of

which was a small elevation called 216.

The town of Doulcon is located in this “punch bowl.” The wooded heights

north of the “punch bowl,” known as Bois de Sassey, were to be saturated with

“yellow cross” gas so as to eliminate any danger from that flank.

The principal mission of the 90th

Division on the first day of the general attack was to capture the wooded ridge

along the left boundary of the Division.

The 360th Infantry was assigned this task. To their right the 359th Infantry was to attack northeast across

Cheline and Etaillon ravines, covering the flank of the 360th Infantry. The front of the 360th Infantry was made

very narrow, and the infantry attack was to be supported powerfully by a deep

rolling barrage of four waves, in addition to gas, smoke, and overhead machine

gun fire, in order that the mission of the regiment might be accomplished as

speedily as possible. As has been

pointed out in the description of the terrain, the Andevanne ridge dominated

the open space which the 359th was to cross; hence that regiment’s advance must

follow the neutralization of the woods to the left. Furthermore, the possession of this ridge would facilitate the

advance of the 89th Division on our left.

The first day’s attack was divided

into two phases. There was an

intermediate objective – Hills 300 and 278 and Cheline Ravine – which all

troops were scheduled to reach by two hours and a half after H hour, and where

all units were to halt, catch their breath, and start off afresh. Then there was the corps objective, the

final objective for the day, which included the heights north and northeast of

Andevanne and the ridge running southeast from Andevanne to Croix St. Mouclen, a

point one kilometer west of Aincreville.

Nothing was left to chance. The

exact rate of advance, with varying speed limits across the open, up the hills,

and through the woods, was set forth in orders, and the exact position of every

unit throughout the attack was planned in advance. On the second day, however, there was no “set piece,” but merely

an “exploitation”; that is, on November 2 each organization was to advance as

far as local successes and the nature of enemy resistance on their front would

permit.

Grand Carre Farm, located northwest of Bantheville on

the high ground in close

proximity to

shell-torn woods. Used by the Germans

for an observation post,

it was the

scene of heavy fighting on October 23 and November 1.

Captured by

the 360th Infantry on November 1.

THE ATTACK ON NOVEMBER 1

A DESCRIPTION of the thrust of

the 360th Infantry is the most logical starting-point of the narration of the

attack of November 1. The 3d Battalion,

commanded by Major J. W. F. Allen, which was to make the assault for the

regiment, took up its position for the jump-off just north of the road leading

northwest from Bantheville, at the point where it loops around the northeast

corner of the Bois de Bantheville. The

2d Battalion in support, and the 1st Battalion in reserve, were in position in

the Bois de Bantheville and the sunken roads to the east of the woods. Some casualties were suffered from an enemy

heavy artillery fire which opened about midnight. The regimental P. C., located in a light shelter in the Bois de Bantheville,

suffered a direct hit about 1:30 A. M.

There were twenty-six casualties in the regimental headquarters

detachment during the night. The

American artillery bombardment, which opened at 3:30 A. M., also brought down

an enemy counter-preparation.

H hour was 5:30 A. M. No sooner had the assaulting wave debouched

from its cover when a terrific machine gun fire poured into the lines. Particular trouble was experienced from the

direction of Grand Carré Farm, which was well situated on the top of the open

ridge. Despite the thoroughness of our

magnificent artillery barrage, many enemy gunners found cover in the shelters

in the vicinity of the farm and came to the surface again in time to catch the

advancing infantry.

But the men of Companies I and K,

forming the assaulting wave, were not to he daunted. Particularly heroic was the conduct of the 2d Platoon of Company

K, which succeeded in capturing the Grand Carré Farm, thus putting out of

action the enemy guns which were holding up the entire line. Led by Sergeant Frank B. Losscher, who was

awarded the D. S. C. for this feat, this platoon maneuvered to the right of the

strong point, and by the use of rifle and rifle-grenade fire and hand-grenades

forced the garrison to yield. Seventy

Germans were rounded up in one dugout, and fourteen machine guns were captured.

Lieutenant

Wylie Murray, Lieutenant James H. Crosby, and Lieutenant John Sieber were

wounded during this fighting.

Lieutenant Murray later died of his wounds. Lieutenant Fleming Burk, commanding Company D, which was

maintaining liaison with the 89th Division, was wounded, Lieutenant Alfred L.

Jones taking command in his stead.

Lieutenant Patrick Edwards and Lieutenant Mason Coney, of the regimental

machine gun company, were evacuated.

After

capturing Hills 300 and 278 the battalion halted on the intermediate objective

for thirty minutes, in accordance with the field order. This delay in the operation afforded the

enemy a breathing-spell during which machine guns and light artillery were

concentrated on the battalion front. At

8: 30 A. M. an attempt was made to resume the advance, but the line was halted

by a withering fire. Twice again a

start forward was made, but the result was so ghastly that the line was halted,

the men taking refuge in shell-holes, and the situation reported to regimental

headquarters. Colonel Price ordered the

2d Battalion to take up the advance.

The battalion was led by Major Hall Etter, who, as a lieutenant, had

been regimental adjutant at Camp Travis.

On coming to France he was made operations officer, and just before the

Division left the St. Mihiel sector took command of the 2d Battalion, Captain

Lyman Chatfield succeeding him as operations officer for the regiment.

The advance got under way at noon. In order to avoid the open ground south of

Andevanne, now being swept by enemy fire, Major Etter maneuvered the battalion

to the west through the Bois d’Andevanne, and went forward into the Bois

Carpiere, north of Andevanne. The

advance was made with such rapidity that enemy machine gunners were captured in

position, together with their guns. The

closeness of the fighting in this wood is illustrated by the extraordinary

experience of Sergeant Alfred Buchanan, Company G, who, upon returning from an

aid station after having his wounds dressed, reached the German lines instead

of our own, but succeeded in escaping and finding his own platoon which he led

with marked courage until wounded a second time. When darkness came the battalion had reached the narrow-gauge

railway running west through the woods from Côte 243. Lieutenant Thomas E. Hazlett, Company E, had been killed shortly

after the attack was launched. Captain

Charles D. Birkhead, Company F, and Lieutenant John S. LeClercq were wounded.

The 1st Battalion, which had moved forward to the right rear of the 2d Battalion, was in position south of Andevanne at 4:30 P. M., when Major W. H. H. Morris, the commanding officer, received orders to pass to the right of the 2d Battalion and seize Côte 243. Owing to the darkness it was necessary for the battalion to advance by compass bearing. Shells from our own artillery, which had been playing on the hill at intervals throughout the day, were bursting on Côte 243 when Major Morris reached the foot of the wooded heights. As telephonic communication with regimental headquarters had been maintained practically continuously, the artillery fire was soon stopped and the battalion moved up the hill. Major Morris established his P. C. there about 8:00 P. M. Captain Gustav Dittmar, Captain Mike Hogg, Lieutenant Lonus Read, and Lieutenant Robert Campbell were wounded during the advance. In mopping up the hill the next morning, a battery of 77’s and two 105’s and fifteen artillerymen, as well as the infantry officers, were captured. The guns were manned by our own artillery and fired on the Germans, there being a plentiful supply of ammunition at hand.

The 1st Battalion, 359th Infantry,

was subjected to an enemy heavy artillery barrage just as the attack got under

way. The advance proceeded rapidly,

despite the machine gun fire which swept the open ridges from the north, the

intermediate objective being reached at 6 A. M. and the corps objective at 9:30

A. M. During this advance Lieutenant

Raymond A. Schoberth, Company B, was killed by a shell fragment near Cheline

Ravine. Early in the morning he had

been wounded by a machine gun bullet, but refused to give up. He was awarded the D. S. C. posthumously.

While

organizing the line of the corps objective, which it was planned to hold

against counter-attacks during the night of November 1, the battalion suffered

very heavily from artillery fire.

Captain John R. Burkett, Company C; Lieutenant Eugene C. Bell, Company

B; and Lieutenant Eugene A. Scanlon, Company D, were killed here.

The

1st Battalion was commanded by Major William R. Brown, who, as a captain, had

served as regimental operations officer during the St. Mihiel offensive. Captain George Knox, who had done excellent

work as regimental intelligence officer, was now operations officer.

During this advance the 2d Battalion

had followed the 1st as support. Some

casualties had been suffered in passing through Bantheville and Bourrut, on

which towns the enemy had laid down a thick barrage; but the company officers,

inspired by the example of Major Tom G. Woolen, the battalion commander, led

the men through without the slightest interruption of the regularity of the

approach formation. In the advance one

platoon of Company F extended too far to the right and came under machine gun

fire. Two guns and their crews of four

men each were speedily captured.

Lieutenant Vernon B. Zacher, commanding the platoon, was awarded the D.

S. C.

At 1:30 P. M. the 2d Battalion

passed through the 1st and continued the advance toward Chassogne Farm. The farm itself offered no resistance, as

the artillery had played havoc with it; but, on reaching this crest, the

battalion found itself under machine gun fire from all sides. Darkness found the battalion’s outposts

along the Aincreville-Villers-devant-Dun road, at the edge of the triangular

woods north of Aincreville. Patrols

brought back the information that the enemy was falling back toward Villers.

The big attack had been a complete

success. By 4:30 P. M. – the hour that the

2d Battalion, 360th Infantry, had achieved its mission for the day – all troops

of the 180th Brigade were on the corps objective, thus breaking the Freya

Stellung. The other divisions in the

1st Army had also succeeded in their missions, and the enemy’s main line of

resistance was broken. In order to make

the most of the exploitation, division orders were issued about 6 P. M. for the

180th Brigade to organize the corps objective line for defense, at the same time

pushing forward fresh troops with the utmost vigor. The 179th Brigade in the meantime had been telephoned to move

forward to position in the woods west of Bantheville.

But, owing to the general

disorganization of the enemy, corps instructions were issued at 11 P. M.,

ordering a further advance on November 2 than was originally contemplated. Hence division orders were also

changed. The 179th Brigade was given

the task of holding the corps objective to guard against counterattacks, and

General McAlexander was directed to use his entire brigade to push the advance

on November 2 to the Halles-Mont-devant-Sassey bluffs.

View taken of Bantheville while it was being shelled on

the morning of the drive, November 1.

P. C. Sterling of the 359th Infantry, one kilometer

north of Cunel.

The officers shown are, from left to right:

Captain Geo. Young,

Colonel E. K.

Sterling, Captain Irwin O. Montgomery,

Captain G. P.

Knox and Lieutenant Chas. P. Hinkle.

BOIS DE RAUX AND HILL 321 TAKEN

THE next morning severe machine

gun opposition was encountered all along the division front. As there was no set program for the day’s

attack, infantry commanders called for artillery support as the centers of

resistance developed. In the sector of

the 360th Infantry – whose fortunes will be considered first – it was found

that the principal volume of fire came from Hill 321, a very small, wooded

eminence immediately northeast of Villers-devant-Dun, and from Bois de Raux, a

patch of woods, about half a kilometer wide, which lay to the west of Hill

321. At 11:30 A. M. an hour’s artillery

preparation was ordered on these two positions preparatory to an attack. In the meantime the 3d Battalion, which had

spent the night on the corps objective, moved up and prepared to pass through the

2d Battalion.

About 1:30 P. M. the 3d Battalion

moved against Bois de Raux and the 1st Battalion began its attack on Hill

321. The 1st Battalion met with

particularly bitter opposition. The

little hill they had set out to take was a solid nest of machine gunners who

had been left in their positions to fight a rear-guard action to the

death. Obedient to command, these men

in field-gray performed their work well, and many of them died at their posts

at the point of the bayonet. But, led

on by the example of Major Morris, who, despite his wounds, exposed himself to

the deadly fire, and pointed out the enemy positions with the walking-stick

which he always carried, by 2:15 P. M. our men had captured the hill and were

moving further to the north.

Both the officers and men of Company

A, which led this assault, displayed marked heroism. The company commander, Captain Charles E. Delano, received a

wound during the action and went to the aid station to have it dressed. While at the aid station he received the

news that Lieutenant George P. Cole had been killed, that Lieutenant Harold H.

Shear was seriously wounded, and that the company was without an officer. He immediately started again for the front,

but was killed on rejoining his company.

Even the 1st Sergeant was put out of action. But the company had been inspired by the fine acts of courage of

its officers, and continued the advance under the ranking sergeant, Robert J.

Moreland, even repelling a counter-attack after it passed Hill 321.

In the 2d Battalion Lieutenant Burr

S. Weaver and Lieutenant Govan N. Stroman were wounded.

359TH INFANTRY CAPTURES

VILLERS-DEVANT-DUN

THE 359th Infantry found its task on November 2 to be

much more difficult than that of the preceding day. In a dense fog at 5:30 A. M. the 2d Battalion, which had taken

over from the 1st Battalion the afternoon of November 1, was formed up as

follows to go after the Hun: Company H to go north to Villers, with Company E

in support; Company F to clear the triangular wood, take Remé Farm, and

continue north, Company G being in support.

Company F did not encounter serious difficulty in the first part of its

mission, but it was brought to a standstill south of the road which runs

southeast from Villers-devant-Dun to Doulcon by fire from the heights “en

Haut,” just north of the road. Company

G took up the advance. Lieutenant John

C. Patterson was shot through the leg, and the command passed to Lieutenant Patrick

J. Murphy, who was the first man of the

company to hurdle the wire.

Company H had its troubles from the

outset. Machine gun positions had been

sited skillfully to cover the road from Aincreville to Villers-devant-Dun. After these positions had been cleared, the

advancing line came under fire from the heights “en Haut,” from the vicinity of

Villers itself, and from the eastern edge of Hill 321. The supporting artillery fired on these

positions for twenty minutes, after which the advance was renewed, and by 2 P.

M. Company H had taken the town and the

crest to the north. These positions

were held under the most trying circumstances A rain of artillery came pouring

down as soon as the Germans were out, and small detachments of the enemy, with

light machine guns, worked forward by rushes up the Ravin du Fond de Theisse

and attempted to retake the town.

Captain H. S. Hilburn, commanding Company H, received the D. S. C. for

his work here.

The counter-attack was delivered by

troops of the 27th German Division, a first-class unit which was put into the

line after four weeks’ rest. According

to prisoners’ statements, this division was put in with the express purpose of

counter-attacking and saving the situation at this point. It went into position between the 88th and

28th German Divisions. Elements of

these three divisions, as well as of a fourth, the 107th Division, had opposed

the 180th Brigade during this operation.

While the enemy units became mixed during the retreat, and the order of

battle by sectors was hard to determine, it is probable that no units engaged

opposite the 90th Division were withdrawn, the presence of new troops

indicating a reinforcement.

In the meantime the 1st Battalion

had received orders to move north as far as Villers, pass through the 2d, and

continue northeast, south of the Villers-Montigny road. In the fog, a group of sixteen Company H men

on the heights north of Villers were overlooked and were not relieved. Lieutenant Walter S. Burke, who was in

command of this small force, had been wounded during the fighting but refused

to give in and maintained his post throughout the night.

The 1st Battalion carried on the

fight, arriving at the edge of the dense Bois de Sassey at nightfall. Forty-two Germans were killed in one nest of

resistance on the brink of the “punch bowl” east of “en Haut.” Corporal T. W.

Butcher, Company C, received the D. S. C. for his feat in capturing three

machine guns after he had been wounded in the back. Major Brown was cited in division orders. He had placed himself in the front line,

rounded up the men who had taken refuge in shell-holes and directed the

operations under machine gun fire. The

bravery of Captain William Fisk, Company D, also inspired the men of his

company to greater action. On this

occasion, as repeatedly on November 1, Corporal Clive C. Collier and Corporal

Glen A. Bell, both of Company D, displayed such soldierly qualities in leading

their squads that they were awarded crosses.

A little strip of woods called “les

Dix Jours” caused the last trouble of the day.

Here Captain Dan C. Leeper, who was posthumously awarded the D. S. C.,

was killed.

The part of the 3d Battalion, 359th

Infantry, in the two days of fighting had been to maintain liaison with the 5th

Division on the right. Before leaving

the Bois des Rappes on the morning of the 1st, Captain Victor H. Nysewander,

Company K, was killed by artillery fire.

During the night of the 1st, two companies connected the right of the 2d

Battalion with the 5th Division at Aincreville, the remaining two companies

being in position with the 1st Battalion on the corps objective. On November 2, Companies I and K entered

Bois de Babiemont, a wood which the 5th Division had experienced great

difficulty in taking from the south.

Patrols from these two companies explored the “punch bowl” and took up

position on Côte 216, two kilometers out of the Division sector. At night they

were pulled back to join their units.

During its two days of smashing

attacks, the 180th Brigade captured eighteen German officers and 789 enlisted

men, of which number a majority of the officers and about 680 men were taken by

the 360th Infantry. A considerable amount of artillery and sixty-eight machine

guns were taken also during the fighting of November 1 and 2. The 3d Battalion, 360th Infantry, captured

two 77’S near Grand Carré Farm, and a detail of artillerymen who had taken

station at Colonel Price’s P. C. turned them on the enemy immediately, there

being a plentiful supply of ammunition at hand. A battery of 77’s located south of Andevanne was abandoned by its

crew after the guns had been incapacitated for further use. A 210-mm. gun was captured by Major Etter’s

battalion north of Andevanne. From the

firing chart of one of the two 105’s captured on Côte 243, Colonel Price found

the explanation of the bombardment of his P. C. early the morning of November

1. It appeared that the shelter had

been spotted by aerial photography, and that the coordinates were turned over

to this gun as one of its targets.

The operations of the 180th Brigade

in breaking the Freya Stellung received the following commendations:

“From Chief of Staff, 1st Army, to

Chief of Staff, 3d Corps, November 1, 22h.20: The Army Commander desires to

congratulate the 3d Corps and express to you his appreciation of the work done

this date. He desires that you express his appreciation to the 90th

Division. Please have this information

transmitted to all organizations as far as possible this night.

DRUM.”

General Hines added to this the

following endorsement: “The corps commander desires to add his congratulations

to those of the army commander to express his appreciation of the gallant work

of your Division to-day.”

View showing Boche machine gun nest and dead gunner,

Villers-devant-Dun.

THE MACHINE GUN BARRAGE

TO this brief exposition of the

infantry action of November 1 and 2 must now be added an account of the part

played by machine guns and artillery.

The machine guns will be reviewed first. The most notable thing about their use was the manner in which

the 345th Machine Gun Battalion supported the advance of the infantry by direct

overhead fire. The terrain was

particularly adapted for effective barrage fire, and the degree of success with

which Major H. R. Kimberling, brigade machine gun officer, exploited this

opportunity established the action as one of the most successful machine gun

operations ever attempted on any front.

Companies A and B, 345th Machine Gun

Battalion, under command of Captain H. B. Irwin, were sited in the Bois des

Rappes, covering the ravines over which the 359th Infantry was to advance; and

Companies C and D, commanded by Captain Louis L. Chatkin, were in the northern

edge of the Bois de Bantheville, from which position they could neutralize the

edge of the Bois d’Andevanne as well as the positions around the town of

Andevanne itself.

Perhaps it will convey some faint

idea of the activity of these barrage guns to state that they fired a total of

approximately a million and a quarter rounds of ammunition. Nor were these bullets wasted. The greater part of this fire was observed,

and a German officer captured the first day testified that it was the most

intense machine gun fire he had ever witnessed. The guns also received credit for silencing two batteries of

enemy artillery – a very unusual feat.

About 11 A. M. November 1, a battery of artillery was located in the

triangular woods just east of Chassogne Farm, and Major Kimberling directed

twelve guns on this spot for twenty minutes, with the result that the battery

ceased to trouble us. A short time

later an observer in the Bois des Rappes saw the Germans trying to get their

guns out of the woods. Fire was again

opened. After the woods were captured,

the artillery pieces were found. The

sides of the horses which were hitched to the caissons were riddled with

bullets. About 1 P. M. another battery

was silenced near the Bois de Babiemont,

Companies

C and B fired from 5:30 to 7: 30 A. M., and then moved forward to join the

infantry. The guns in the Bois des

Rappes, however, continued firing for a period of nine and a half hours on

November 1 without stopping. Again, on

the morning of November 2, these same guns fired for forty-five minutes on

targets in the sector of the 359th Infantry, at a range of approximately 3000

meters, with good effect.

This wonderful result was achieved at the expense of only four men killed and twenty-one wounded. The slight casualties were due to the precautions which Major Kimberling took to have all men dig in properly before the action opened. The major assembled not only his officers, but his section leaders as well, at his headquarters at Nantillois several days before the attack, and there he explained in detail everything that was to be done. A model trench and machine gun emplacement, with section belt refilling station, had been dug at Nantillois. On the night of October 28 the men began digging similar emplacements for their barrage positions. During the daytime the range to all conceivable targets was taken, the compass bearings obtained, and charts made for each gun in order that all guns might be directed on the same target at a minute’s notice, if it should be so desired.

The gunners who fired with such

marvelous accuracy on November 1 had been without sleep for several days and

nights. In addition to the work

involved in digging in, there was an immense amount of ammunition to be carried

forward from the dumps to the guns. The

left group of gunners, in the Bois de Bantheville, were forced to carry 300,000

rounds from trucks which became stalled south of Bantheville.

But the 345th Machine Gun Battalion

was only half of the machine guns participating in this action, The other

gunners performed their tasks with equal distinction. The entire machine gun plan had been coordinated by Lieutenant

Colonel Ernest Thompson, division machine gun officer, who followed the

principle of keeping the guns out of the front wave, and, instead, searching

out commanding ground from which the guns could aid the infantry advance by

delivering direct overhead fire. The

343d Machine Gun Battalion was in readiness in the Bois de Bantheville before H

hour, and at 5:50 A. M. went over the top behind the assaulting infantry

wave. Company A established itself on

Hill 278, from which point it fired on the centers of resistance around

Andevanne. One gunner alone fired eight

boxes of ammunition on the edge of Bois d’Andevanne, with excellent

results. It was the plan for Company B

to move forward to Grand Carré Farm to cover the advance of the right regiment,

but only the 2d Platoon was able to arrive at the objective intact. The 1st and 2d Platoons, as well as the

Headquarters Platoon, suffered severely from shell fire. During the night of the 1st the 343d Machine

Gun Battalion moved forward and took up a defensive position on Côte 243. On November 2 the battalion assisted the

advance of the 1st Battalion, 360th Infantry, against Hill 321, and had a part

in breaking up the enemy counter-attack in that region. Despite its rapid movement, the battalion

maintained constant telephonic communication with Major Kimberling throughout

the action.

The regimental machine gun companies

of the 359th and 360th Infantry were attached to the assaulting battalions of

their regiments, advancing by bounds and covering the advance of the infantry

wave.

Although not an organic part of the

Division, the 155th Field Artillery Brigade, which supported the Division in

the attack, won for itself a warm place in the hearts of commanders, staffs,

and doughboys alike. Every member of

that brave organization, from Colonel Robert S. Welsh, the brigade commander,

who was killed by shell fire the morning of November 5 on the road between

Villers-devant-Dun and Montigny, down to the humblest gunner who assisted in

dragging his battery into position with ropes the night before the attack, has

the heart and soul of a soldier.

The 2d Battalion, 313th Field

Artillery, commanded by Major John Nash, particularly distinguished itself in

the eyes of the infantry. The regiment,

commanded by Colonel O. L. Brunzehl, was in direct liaison with General

McAlexander, and the 2d Battalion furnished the forward guns which were to

follow up and support the infantry advance by direct fire. Immediately after the infantry jumped off,

the batteries prepared to move forward.

In order to reach their positions south of Grand Carré Farm and behind

Ridge 270, it was necessary to cross the open ground under both machine gun and

artillery fire. Going first at a trot

and then at a gallop, Batteries D, E, and F went into action in a spectacular

manner that rallied the infantry and caused men to remark, “With such artillery

we can go through hell.” Captain

Anderson of Battery E was killed in this noble charge in the face of machine

gun fire.

There were only two hours of

preparatory fire before the attack.

However, during the night non-persistent gas had been fired into the

Bois d’Andevanne. The rolling barrage

under which the infantry advanced at H hour was exceedingly effective. This barrage, which was 1000 meters deep and

1200 meters wide, consisted of four waves, the first two being high

explosive. It was fired by seventeen

batteries of 75's and six batteries of 155’s.

The effectiveness of this fire was later revealed by the number of

machine gunners found dead in their fox-holes.

As the smoke made observation of the bursts impossible, different

heights of bursts were used. In

addition to this barrage, the advance of the 360th Infantry was aided by raking

fire on Grand Carré Farm, Côte 243, and other dangerous points. There was no rolling barrage in front of the

359th Infantry, the accompaniment consisting of raking fire on Cheline Ravine,

Chassogne Farm, and other suspected enemy positions.

The 2d Battalion, 314th Field

Artillery, was designated to fire on targets of opportunity and surprise. It was pulled by drag-ropes into the

northern edge of the Bois des Rappes, and there awaited its chances. But the fog and smoke so completely obscured

all observation that the battalion could render but little service.

Colonel William Tidball, who

succeeded Colonel Welsh in command of the brigade, commanded the heavy

regiment, the 315th Field Artillery. In

addition to the organic units of the 155th Field Artillery Brigade, the 16th

Field Artillery and the 250th R. A. C. P. (French) were under the divisional

artillery commander.

Before the action Captain Francis

Tweddell of the 305th Ammunition Train organized a detail of twenty-four men to

handle captured guns. Of the thirty-two

guns captured, four 77’s were used against the enemy, firing a total of 226

rounds, and two 105-mm. guns, firing a total of 275 rounds. A battery of 105’s put in operation on the

heights south of Mont-devant-Sassey was given the name of “Hindenburg.” The

principal difficulty found by Captain Tweddell was that the guns had been

stripped of their sights or disabled by the retiring enemy, or that there was

no transport available to haul them into range.

As in the St. Mihiel operation, the

gas troops were unable to be of great service.

Company F, 1st Gas Regiment, attached to the 90th Division, installed

four 4-inch Stokes mortars in the northern edge of Bois de Bantheville and

twenty gas projectors in the Ravin-dit-Fosse-de-Balandre, between the wood and

the town of Bantheville, and planned to assist the infantry with smoke screens

and lethal gas. But owing to adverse

wind conditions no gas was fired.

However, the mortars were able to fire thermite on enemy targets in the

woods south of the Bois d’Andevanne and Grand Carré Farm before H hour, and at

H hour to create a white phosphorus smoke screen. But about twenty minutes after the advance started, the Stokes

mortar section was caught by enemy shell-fire and broken up, five men being

killed and thirteen wounded.

The exploitation on November 2

turned out to be as costly as the set attack of the first day. In consideration of the urgent need of

pressing the enemy without respite, and owing to the fact that the 180th

Brigade had suffered heavy casualties and was nearing exhaustion, a division

order was issued at 2 P. M. directing the 179th Brigade to relieve the 180th

Brigade and carry on the latter’s mission of exploitation.

But, as on the previous night,

further information regarding the great success of the divisions further to the

west brought about a change in the army’s plans. The enemy was now in full retreat and was withdrawing so fast

that the 4th French Army, to the left of the 1st United States Army, had lost

contact altogether. The French troops

had entered Boult-aux-Bois, just east of the Argonne Forest, there making

connection with the Americans.

The front of the 90th Division was

the pivot of this retreat; Hill 321 and Villers-devant-Dun were the hinge which

had held fast while the door was swinging backward. So it was decided to attack in full force the morning of November

3 in order to smash this hinge.

Field Order No. 16, 90th Division,

specified that the 179th Brigade would make this attack, while the 180th

Brigade would continue to hold the line which it had established during the day

– Bois de Raux, Hill 321, Ravin de Theisse, and Les Dix Jours.

The objective of the attack was the

heights from Halles to the Meuse.

Simultaneously the 5th Division was to attack and then to cross the

Meuse.

After midnight of November 1-2, and

during the morning of the 2d, the troops of the 179th Brigade were moving

forward to occupy the corps objective.

The 357th Infantry got into position on the right, but the 1st

Battalion, 358th Infantry, captured four prisoners and suffered some losses from

shell-fire before getting into place.

During the night of November 2 the battalions of both regiments

continued the march to get in position for the passage of lines through the

180th Brigade.

GREAT ADVANCE ON

NOVEMBER 3

CONSIDERABLE difficulty was anticipated in piercing the dense

woods on the Halles-Montigny heights.

The attack was to be made at 8 A. M., November 3, by the 358th on the

left and the 357th on the right. During

the night the artillery had bombarded enemy positions with gas, and a rolling

barrage advancing at the rate of 100 meters in eight minutes was put down in

front of the infantry. The 343d Machine

Gun Battalion was attached to the 179th Brigade.

Imagine the general surprise, then,

when the troops entered the woods without a hostile shot opposing them. The bursting of our own shells among the

trees, as the barrage crept forward, was the only artillery firing to be

heard. The Germans had made good their

escape across the Meuse during the night.

Our men went romping through the forest, and at 11: 30 A. M.

Lieutenant-Colonel Waddill, second in command of the 357th Infantry, sent back

this message from the heights south of Montigny: “No enemy in sight; no

artillery; good view for miles.”

As soon as full information

concerning the German withdrawal had been received by the 3d Army Corps, orders

were issued by headquarters of that corps directing the 90th Division to keep

up vigorous contact with the enemy and to push detachments, accompanied by

machine guns, across the Meuse River to protect a crossing. This order was immediately telephoned to

General O’Neil, who made plans accordingly.

The 357th Infantry prepared to put a force across the river at Sassey,

while the 358th Infantry exploited toward Stenay.

This was about noon. But during the afternoon another corps order

was issued, changing the previous plans, and providing that the 90th Division

would hold the bulk of its forces on the Halles-Montigny heights, while the 5th

Division, on the right, developed a bridgehead at Dun-sur-Meuse. The 90th Division was to aid with the bulk

of its artillery the establishment of this bridgehead, and was also to locate

and protect any undestroyed bridges over the Meuse within its sector.

MEUSE BRIDGES

DESTROYED BY GERMANS

IN the meantime the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry, was

advancing toward Sassey-sur-Meuse and came under machine gun fire from east of

the river. It was found that a storm

arch had been blown out of the bridge at Sassey, leaving a gap of about sixty

feet, and that the foot-bridges at Sassey and Saulmaury were destroyed. The 2d and 3d Battalions assembled south of

Montigny. The P. C. of the 179th

Brigade was established at Montigny at 8:30 P. M., moving from Grand Carré

Farm, which had been left far behind in the rapid advance. The P. C., 357th Infantry, was also

established there. During the night

patrols from the 357th Infantry went up the river as far as possible without

entering the heavily gassed area in the Bois de Sassey, and down the river to

Wiseppe, where machine gun fire was encountered. The 358th Infantry assembled in the Bois de Halles, but the

regimental P. C. was not able to stay in Halles the afternoon of the 3d on

account of a gas concentration. It was

also found that a number of machine gun nests still remained north and east of

Halles, and approaches to the town were swept by their fire.

The period from the time our

victorious battalions reached the bluffs overlooking the Meuse River on

November 3 until definite orders were received on November 9 to make a crossing

and take up the pursuit, was one of great uncertainty. On October 30 the 3d Army Corps had issued a

“plan in case of withdrawal of the enemy,” which was to be effective when the

Germans began a general retirement. This

order provided that the 90th Division would cross the river at Stenay and

pursue almost due east toward Montmédy.

That this would be put into force was generally expected. During the afternoon and night of November 4

the 1st Battalion, 358th Infantry, moved up to Côte 205, a height half-way

between Halles and Laneuville (the latter town being across the river from

Stenay), and sent patrols into Laneuville, where similar patrols from the 89th

Division were met. On November 5 the P.

C. of the 358th Infantry moved to Boulain Farm, occupying the former P. C. of a

German division commander, and the 2d Battalion moved to Bois de Boulain in

support of the 1st Battalion. On

November 6 the 3d Battalion filtered across the Wiseppe River and took up a

position near the 1st and 2d Battalions in the southeastern edge of the ForLt de Dieulet.

Likewise, the artillery was moved forward to cover a crossing in

that vicinity. During the night of

November 3 and the morning of November 4 the 313th and 315th Field Artillery

regiments were moved to positions east and south of Villers-devant-Dun in order

to aid the 5th Division in establishing the Dun bridgehead. But on the night of November 6, both

regiments moved forward again to positions near Halles, the 313th batteries

being located near the town of Halles and in the Chenois Woods, and the 315th’s

guns going into the ravine running north from Le Fourneau, just west of Bois de

Halles. The 314th Field Artillery

regiment, in liaison with the 179th Brigade, went into the Bois de Mont on the

morning of November 4, along the road running west from Mont-devant-Sassey, and

remained there during this period.

Engineering

preparations were also made for this crossing.

All the area between Laneuville and Stenay was very low, and the road

connecting these two towns was on an embankment. Between the Stenay railway station, which is nearer Laneuville

than Stenay itself, and the Meuse River proper, there were a number of small

streams, including the Wiseppe River.

This Laneuville-Stenay roadway was in the nature of a long approach fill

leading to the bridge proper, and there were five openings in the fill, varying

in length from thirty to eighty feet, over the five streams. A reconnaissance showed that not only had

the main bridge been destroyed, but the structures spanning the small streams had

also been blown up.

The stream channel had been flooded by locking the gates of the canal and by felling trees along the river bank. As the flooded area was about a kilometer wide, it was impossible to cross except on the approach; so preparations were made to bridge its gaps. Company E, 315th Engineers, was assigned to this work, and the necessary material for the job was hauled from a German dump at Montigny to Laneuville by the trucks of the 315th Engineer Train and trucks of the 343d Machine Gun Battalion. It was expected to cross the river proper by pontoons, and a pontoon train was sent up by the army. But the change in plans rendered this work unnecessary, and the river was bridged by other engineers after the armistice.

The engineering work was directed by

Colonel Jarvis J. Bain, who was assigned as division engineer when Colonel Pope

returned to the United States.

Although the exact direction of the

next advance was uncertain, there being an intimation from higher headquarters

that the Division might push north on the west side of the river instead of

crossing, General O’Neil continued to make preparations for getting across the

Meuse in case a forced crossing were ordered.

Several boats and rafts were constructed by the 315th Engineers and men

of the Brigade.

A bridge across the Meuse River, between Laneuville and

Stenay,

which was blown

up by the Germans in their retreat.

Bridges over the Meuse River, showing damage left by

the Germans in their retreat.

PATROLLING THE MEUSE RIVER

THE orders of the corps between

November 4 and the night of November 7 stressed the reconnaissance of river

crossings in the vicinity of Stenay, as well as pushing patrols across the

stream to keep contact with the enemy.

During this time the 5th Division was crossing the Meuse further south

and was developing a bridgehead at Dun-sur-Meuse, while the 89th Division and

divisions further to the west were cleaning out the enemy on the west bank of

the river as far north as Sedan. The

5th Division effected a crossing on the night of November 4-5 at Brieniles, and

on November 5 the 32d Division, which had been in 3d Corps reserve behind the

90th Division, sent a regiment across to work on the right flank of the 5th

Division. Several temporary bridges had

been constructed, and a bridge capable of carrying heavy trucks at

Dun-sur-Meuse was in operation on November 6.

This period of waiting sorely tried

the patience of the men, who were eager to keep after the Boche. And the longer the halt lasted, the worse

the situation became. Artillery fire on

Halles, Montigny, Mont, the road from Villers-devant-Dun to Montigny, and other

points daily became heavier; bombing planes paid nightly visits to practically

all the towns holding troops, including Villers-devant-Dun, to which town

Division Headquarters had moved on November 3; and the machine gun positions

east of the Meuse were strengthened.

The last enemy machine guns were not

cleared out of Wiseppe until the night of November 4. At daybreak that morning Captain DeWitt Neighbors, Company E,

357th Infantry, had advanced against the town, but was forced to withdraw after

having fourteen men killed and thirty-eight wounded. Lieutenant Thomas S. Frere was badly wounded. The withdrawal was so hasty that six wounded

men were left behind. These men were

picked up by the Germans and taken to a building in Wiseppe, where they were

given first-aid treatment, food, and wine.

They were found again when the town was re-occupied by our troops on

November 6. On the afternoon of

November 4, Companies E and H, 357th Infantry, again advanced and reached Hill

206, northwest of Wiseppe, but the town was avoided, as the Germans were then

shelling it very heavily.

The territory between the bluffs and

the river is as smooth as the top of a table, and any movement drew enemy

fire. Patrols attempting to investigate

the condition of the river bank and crossings were sniped at, not only by

rifles and machine guns, but also by one-pounder guns and 77’s. The information desired was obtained under

the most trying circumstances and at the greatest possible risk. Imagine, for example, the situation of

Lieutenant Frank Feuille, 358th Infantry, who went out on November 6 in broad

daylight to investigate river crossings east of Wiseppe. He was forced to cross the Wiseppe River, in

plain view of the enemy, and after every movement there went whizzing by his

head a one-pounder shell from a gun on the east bank of the Meuse.

Attempts to cross the Meuse were

costly. On the night of November 5 a

patrol from the 357th Infantry placed a ladder across the gap in the cement

bridge at Sassey, but the fire on the bridge was so heavy that no crossing was

made. Lieutenant Wendell F. Prime,

attached to Company L, was killed the same night in attempting to cross near

Saulmaury. The first crossing was made

on the night of November 6, opposite Villefranche, in a boat.

Patrols of the 358th Infantry were

particularly active in investigating approaches to Stenay. On the 8th a patrol led by Lieutenant Rufus

Boylan, 2d Battalion, succeeded in wading across the five streams between

Stenay station and the main bridge, and brought back much valuable

information. On November 6 one platoon

of the 358th Infantry took station in Laneuville. Engineers who accompanied the other troops removed no less than

twenty-five treacherous mines from the buildings in which the men were later

billeted.

On November 7, while the 5th

Division was engaged in operations which resulted in the capture of Côte Saint

Germain, a formidable height east of Sassey, patrols from the 1st Battalion,

357th Infantry, crossed at Sassey and went about two kilometers north along the

river. Due to the advances on the east

bank, the enemy were evacuating the lowlands between the river and the

canal. This patrol also established a

post in a stone building about 750 meters southeast of Sassey, in the angle

formed by the canal and a bend in the river.

During the night a detachment from the 5th Division came up to this

point and a joint post was established.

A very amusing incident occurred

about 5:20 o’clock that afternoon. Five

ambulances from the 5th Division, which had evidently lost their direction,

went too far along the Route Nationale, which runs north from Dun-sur-Meuse to

Stenay, and were captured north of Sassey.

The ambulance drivers’ plight was observed by Lieutenant R. H. Peake,

Company C, 357th Infantry, who was inspecting his outposts, and also by an engineer

officer of the 32d Division, who had begun work about noon that day repairing

the Sassey bridge. Prompt action by

these two officers, operating on both sides of the roadway, succeeded in

recapturing the ambulances. Four

Germans, with three light machine guns, were also captured and sent back to the

5th Division in the ambulances under guard of two men from Company C.

On November 7 the Division received

orders to organize its sector for defense.

Division orders were accordingly issued, stating that the 179th Brigade

would hold the outpost line along the Meuse and the main line of resistance

along the heights from Halles to the Meuse.

The 180th Brigade continued in reserve.

This brigade had followed up the advance on November 3, the troops of

the 359th Infantry going into barracks south of Montigny, and the 360th

Infantry bivouacking in the Bois de Montigny.

The brigade P. C. was at Villers-devant-Dun, the 359th P. C. at

Montigny, and the 360th at St. Marie Farm, the second farm of that name to play

a part in the Division’s history.

The physical condition of the men of

the 360th Infantry was very serious at this time. The physical strain of the severe fighting in piercing the Freya

Stellung; the damp, unhealthy surroundings in which they found themselves in

the Bois de Montigny, without sufficient blankets or overcoats, as all packs

had not yet been brought up; impure water and cold meals at uncertain hours –

these were some of the circumstances which made nearly forty per cent of the

regiment victims of diarrhea, and twenty per cent, patients with sub-acute

bronchitis. In view of these

conditions, it was decided to put the men in better billets. The morning of November 7 they marched to

billets as follows: Regimental P. C. and 3d Battalion, Andevanne; 1st

Battalion, Villers-devant-Dun; and 2d Battalion, Bantheville.