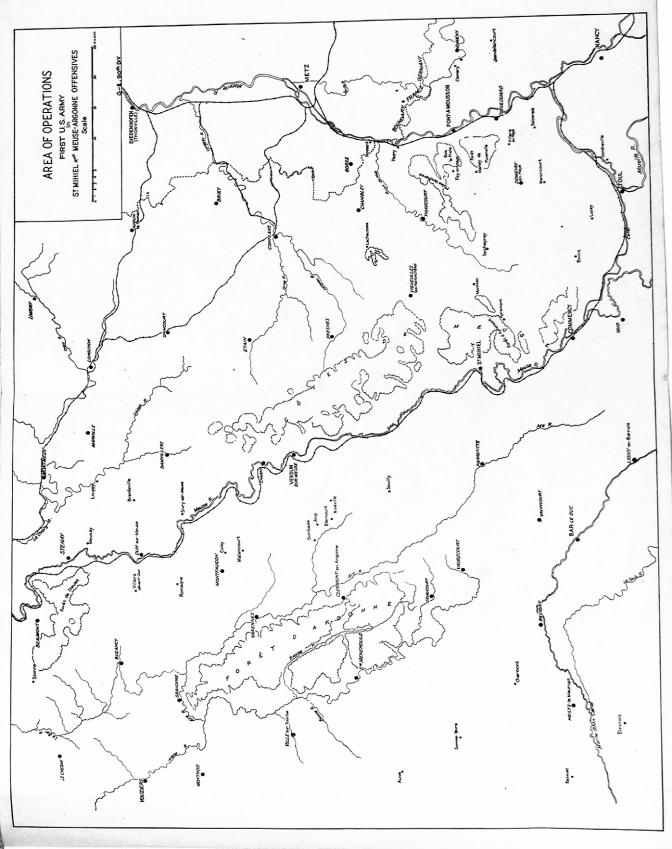

THE PERIOD OF STABILIZATION

THE period of stabilization from

September 16 until the relief by the 7th Division on October 10 was one of the

most trying in the Division’s history.

A short time before the relief took place every one was beginning to

settle down fairly comfortably, but the organization of the new sector, which

took the name of “Puvenelle” from the huge forest, was by no means a simple

task.

In the first place, the defense of

the sector had to be prepared. Colonel

F. A. Pope, the Division engineer, immediately sited the main line of

resistance, which was to run from the western boundary of the Division along

the south bank of the ravine which cut through the middle of the ForLt des Vencheres, thence along the north edge of the

Bois de Friere to La Poele, the maze of German trenches which had become famous

in the fighting on September 12, here connecting with other German trenches,

the Tranchée de la Combe and the Tranchée de Plateau, which were faced in the

opposite direction. This work was

supervised by the engineers, but most of the manual labor had to be done by the

doughboys, who were already exhausted after four days’ fighting. Colonel John J. Kingman, chief of staff,

personally took much interest in this work, and his engineer training was of

great value in drawing up the plan of defense.

Even more difficulty was experienced

in the outpost zone. The men had not

yet learned that digging a hole and crawling into it was just as important a

part of modern warfare as shooting the enemy.

They were perfectly willing to go out on patrols, or make a new advance,

if necessary, but trench digging did not appeal to them as the soldierly thing

to do. The consequence was very

serious, as all the front areas were very heavily shelled, and the men were

without adequate protection from shell fire.

The Germans were well acquainted with every path and lane through the

Bois des Rappes, and were very clever in calculating just the right hour to

plaster them with high explosives.

The line of resistance of the

outpost zone first ran through Les Huit Chemins, but about September 20 it was

pushed further forward nearer the edge of the woods. These positions were finally completed and wired, and before the

Division left the area the northern part of the Bois des Rappes, with its

innumerable “fox holes” looked like a gopher community.

The 357th Infantry had considerable

trouble on its left flank due to the fact that the78th Division, which had

relieved the 5th Division, found difficulty in crossing the open ground north

of Hill 361.4. The Bois du Trou de la

Haie was held by the enemy, and it was very easy for patrols, with machine

guns, to slip into the Bois des Rappes under cover of the strip of woods, less

than 100 meters wide, connecting the Bois du Trou de la Haie and the Bois des

Rappes.

Every effort was made by the

Division staff to give the men who had gone through the fight a bath and clean

clothes as soon as possible. The main

baths and delouser were located at Griscourt.

G-1 also established supplementary baths at Gezoncourt, Jezainville, and

Camp Jonc Fontaine, securing underwear by sending to the big United States

laundry at Nancy, where worn garments were exchanged for clean ones. The policy was adopted by G-3 of making

battalion reliefs weekly, the reserve battalion of the 180th Brigade going to

Griscourt and the reserve battalion of the 179th Brigade taking station at

Gezoncourt. But, at best, there was a

long wait for the majority of the men.

During the fighting many officers had lost their bedding rolls and had

no clothes except the ones which had been torn to shreds by barbed wire. Before the men went over the top, their

packs were assembled in dumps. G-1

transported these packs to points near the front line as fast as possible, but

in many cases the rain and mud had rendered the blankets and overcoats

unserviceable.

The battalions at Griscourt and

Gezoncourt spent most of the short week allotted them resting, getting a bath,

and procuring new clothes and equipment.

However, G-3 took this opportunity also to introduce a short program of

training emphasizing through close order drill the restoration of discipline

and smartness, on which the Division had prided itself in the training areas,

but which had badly suffered during the period of fighting. Liaison problems with aëroplanes were

conducted also.

DIVISIONAL SECTOR WIDENED

THE divisional sector was twice widened: first, to the

right, by taking over from the 82d Division, on the night of September 16-17, all

territory to the Moselle River. The

night of September 18-19, the 82d Division was relieved by the 69th (French )

Division. On October 4 the 78th

Division, on the left, was withdrawn from the line, and its sector was divided

between the 89th and 90th Divisions.

This relief was effected by withdrawing the 358th Infantry from line and

moving the regiment to the west to relieve the entire 156th Brigade, while the

357th Infantry and the 359th Infantry closed in and made connection, each of

the latter two regiments taking over a part of the old 358th Infantry’s

line. This relief extended the Division

front to a point about a kilometer and a half south of Rembercourt,

approximately eleven kilometers on a straight line from Vandieres, the right

flank (and much more than eleven kilometers if all the bends in the line were

considered).

With this extension, the Division

sector included the town of Viéville-en-Haye and the Bois d’Heiche and Bois la

Haie l’EvLque. The 358th

Infantry moved to the new area and made the relief during the daytime, the men

filtering in small numbers across the open space north of Viéville.

The night of the 4th the 153d Field

Artillery Brigade was relieved so that it could join its division, the 78th,

and proceed to the Meuse-Argonne front.

Its mission was taken over by the 5th Field Artillery Brigade, most of

the young officers of which were from Texas.

The 19th Field Artillery Regiment was in liaison with the 180th Brigade,

and the 20th Field Artillery Regiment supported the 179th Brigade.

On September 29 and October 6 the

depleted ranks of the organizations were partially filled by replacements,

approximately 1000 men arriving from depot divisions on each of those

dates. On three other occasions the

Division had received replacements, once at Aignay-le-Duc (300 on August 2) and

twice at Villers-en-Haye before the attack (255 on August 30 and 400 on

September 5).

TROUBLE FROM RIGHT

FLANK

THE greatest source of trouble during the period of

stabilization was the German artillery located on the east side of the

Moselle. Owing to the fact that the

divisions to the right of the 90th had not advanced during the St. Mihiel

offensive, our flank was ‟in the air” and open to enfilading fire. In fact, German guns on the east bank could

he located further south than our positions in the Bois des Rappes and shoot

our men in the back, as it were. Our

supporting artillery was several times accused of firing “shorts” before the

nature of this enfilading fire was understood.

Despite the hardest efforts of the 153d Field Artillery Brigade at

counter-battery, this fire against our right flank, directed by German

observers on the heights at Vittonville, continued to cause casualties as long

as the Division remained in the sector.

Lieutenant Fred H. Morgan, Company C, 357th Infantry, was struck and

killed by a 77-mm. shell the day after he returned from school. His battalion was in the outpost position,

but he had stopped on the line of resistance, as a relief was to take place the

next day. Lieutenant Benjamin E. Irby,

3d Battalion gas officer, was shot through the shoulder while on a patrol.

This continual shelling made the

question of supply very difficult. All

transport was forced to cross what was known as “Death Valley” through Vilcey-sur-Trey

or Villers-sous-Preny, which was under constant observation during

daylight. On the morning of September

16, the Supply Company of the 357th Infantry, which had kept well up with the

advancing infantry, was caught in shell fire near St. Marie Farm, and many

horses were killed and wagons knocked out.

A new road built from Montauville through the Bois-le-Pretre, and then

by way of Villers-sous-Preny into the Bois des Rappes, was used by the 359th

Infantry. In crossing “Death Valley”

eight horses of the Supply Company were killed, and twelve more were lost in

the Bois des Rappes.

The kitchens were located near

springs in order that water might be had.

For example, those of the 358th Infantry were near the large spring in

the southwest corner of Bois de Villers, and the 359th’s in the Bois de

Chenaux. These spots were well known to

the Germans, who correctly guessed that our men were making use of them, and

they were constantly shelled, especially with gas, thus running up the number

of casualties among the “kitchen police.”

PATROLLING AND

ARTILLERY ACTIVITY

WITH the advent of the American army in force, Marshal

Foch had decided that there would he no more “quiet fronts.” This momentous

decision on the part of the Allied Generalissimo was quite in keeping with the

opinion of even the humblest private, who had no desire to sit down in foreign

trenches and wait for something to happen.

The divisional front was far from

quiet. Every opportunity to harass the

Germans was seized. Almost nightly patrols,

often in strength, went out from each regimental front with the mission of

penetrating as far as possible into the enemy lines, securing information about

their defenses, and capturing prisoners.

A total of eleven Huns were bagged during this period of stabilization

by these small patrols.

Seven of these prisoners were

captured by the 359th Infantry. The

aggressive spirit of the officers composing these nightly raiding parties is

illustrated by the action of Lieutenant (later Captain) James A. Baker, Jr.,

who never failed to bring back a prisoner.

One morning, about 3 A. M., after an unsuccessful patrol had returned to

our line, Colonel Sterling directed that another patrol be sent out. Lieutenant Baker was given this patrol and

returned before daylight with prisoners.

Patrols using the short shotguns

also succeeded in inflicting casualties on German outposts. The majority of prisoners were taken by

surrounding outposts in front of Preny and along the Ravin Moulon, which flowed

into the Moselle south of Pagny-sur-Moselle.

The town of Pagny itself was an object of curiosity. It was known that a garrison of considerable

size was sheltered in its cellars. Some

daring adventurers worked their way up the Tranchée de la Remise, an old German

trench running almost due north from Côte 327, and reached the very outskirts

of Pagny, where they could see and hear what was occurring within buildings.

The artillery was as aggressive as

the infantry, and kept up the spirits of the latter by harassing the Hun. The men remained cheerful, despite the

enfilading fire which continually jeopardized their lives, as long as they

could count just as many shells going over their heads in the direction of

Bocheland. The intelligence personnel

of the regiments worked in coöperation with the artillery, the forward

observers, particularly on Côte 327 and Croix des Vandieres, spotting many

targets. Direct telephone connection

with the artillery made it possible to notify the batteries in time to lay the

guns and open fire on moving troops and transport which appeared within

range. The observers of the 360th

Infantry, under the direction of Lieutenant Prescott Williams, intelligence

officer, became expert at this.

Unfortunately Lieutenant Williams was evacuated on account of sickness

before the regiment left the sector.

The Division observation station, under Sergeant Owen Covel and Sergeant

Arthur C. Stimson, which had become famous under the code name of “Dottie,”

worked first from Côte 327 and then returned to Mousson Hill, an eminence just

east of Pont-â-Mousson, from which the spires of Metz can be seen on a clear

day.

On October 2 the north edge of the

Bois des Rappes, particularly in the zone of the 2d Battalion, 358th Infantry,

was saturated with mustard gas. That

day 150 men were evacuated from the 2d Battalion. Notwithstanding these losses, the battalion continued to hold the

line. The effects of the gas were

horrible beyond description, some being blinded for life, others disfigured by

the effects of the acid on parts of the skin which the liquid had touched. In addition, practically every man in the

battalion, although continuing to do duty, was weakened by inhaling the

fumes. On October 4 the 2d Battalion

moved over to the west, going into the front line in the sector taken over from

the 78th Division. As a result of the

gas the men could not refrain from coughing, sentries on outpost duty sometimes

giving away their position as a consequence.

The evil effects of this gas

bombardment were felt even after the Division moved into the Meuse-Argonne

sector. Major Earl T. Brown, regimental

surgeon, claimed that the battalion was unfit for duty, and upon examination,

on October 18, three officers and 130 men were evacuated as post-gas

cases. This made a total of

approximately 300 men who were put out of action by the gas attack, not to

mention many others who were rendered unfit for the arduous duties of a

soldier.

RAID OF SEPTEMBER

23

IN order to impress upon the enemy the offensive spirit

of the Allied forces, the army planned a series of raids all along the

front. The date for the 90th Division

raid was set for the night of September 23-24.

It was decided that this raid should be staged in the 357th Infantry

sector, as here the opposing lines were closest together and the point of the

Bois des Rappes furnished an excellent forming-up place.

The raid was successfully executed

by the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry, under command of Captain Aubrey G.

Alexander, supported by the 153d Field Artillery Brigade. The raiding party crossed two bands of wire,

reached the second line of trenches, captured five prisoners, and came hack

intact with valuable information regarding the famous Hindenburg line. The battalion suffered twenty-four

casualties, only a few of which were serious, none being killed. The majority of the casualties were received

from artillery fire in the vicinity of Les Huit Chemins as the battalion was

going into position.

In this operation the trenches

Grognons and Pepinieres were penetrated and a section about one kilometer long

of each of them mopped up. There was no

artillery preparation, but a box barrage protected the raiders until two green

V. B. rockets fired by Captain Alexander gave the signal that all our men had

returned to our lines. Companies B and

D, 344th Machine Gun Battalion, put down a barrage, lasting one hour, with

twenty guns. A dummy raid effected by

artillery and machine gun fire on Preny furnished a diversion which kept the

enemy guessing as to where the blow would fall.

DEMONSTRATION OF

SEPTEMBER 26

WHILE the 90th Division did not enter the Meuse-Argonne

front until October 22, it played a part in the offensive on September 26 the

first day of the big attack – which will long be remembered. The 1st Army decided that simultaneously

with the attack west of the Meuse, demonstrations would be made by the

divisions between the Meuse and the Moselle.

In addition, all divisions east of the Meuse under the 1st Army command

were to be held in readiness to attack or take up the pursuit in case the enemy

showed signs of weakness or withdrawal.

On the night of September 24 the

order of the 4th Corps was received directing the 69th (French) Division, east

of the Moselle, and the 90th, 78th, 89th, and 42d Divisions, west of the

Moselle, to make raids simultaneously, starting on D day at H hour, and

penetrating through the enemy’s zone of outposts to the hostile line of

resistance. In a conference with the

brigade commanders that same night at Villers-en-Haye. General Allen decided upon the plan for the

90th Division raid.

It was decided that the raiding

party should be made up of troops from each brigade. The 179th Brigade’s quota was about 500 men. For this operation Companies B and D of the 358th

Infantry were raised to full war strength of 250 by attaching men from other

units to fill up the depleted ranks.

The raiding party of the 180thBrigade consisted of Companies F and H,

359th Infantry, under the command of Captain Fred N. Oliver, Company E, and

Companies E and F, 360th Infantry, commanded by Major Charles E. Kerr. Lieutenant-Colonel R. T. Phinney, 359th

Infantry, was in command of the entire 180th Brigade detachment.

That the Germans had anticipated

with uncanny shrewdness the nature of our operations was proved in the

preparations they made to forestall the attack, and was later further verified

by the statements of German officers of the 123d Infantry Division, which held

the line at this point. The German

outposts had been doubled by bringing up an additional battalion, and a half

hour before midnight of September 25-26, while the raiding parties were moving

to their assembly positions, a terrific barrage came down upon our lines. The companies of the 360th Infantry suffered

especially, and were unable to reach their position until 4 A. M. The enemy also started out early in the

night to test out our positions with patrols, which undoubtedly carried back

information as to our dispositions and intentions. For the purpose of the raid, the companies of the 359th had taken

up a position in front of the 358th sector, about 100 meters beyond the edge of

the Bois des Rappes. They reached their

places about 9:30 P. M. and were almost immediately attacked by a large German

patrol. Later in the night their position

was again strongly assailed. The 179th

Brigade detachment encountered German patrols in the Bois des Rappes, and were

forced to drive them out in order to reach their jumping-off place near the

point where the road from Huit Chemins to Grange-en-Haie Farm debouches from

the woods. They were in place about a

half hour before midnight, Captain George B. Danenhour, commanding the two

companies, making his P. C. in the hospital at the edge of the woods.

Just at the zero hour, 5:30 A. M.,

another violent barrage fell between the attacking and support companies of the

180th Brigade. And no sooner had the

assaulting waves debouched when they were swept by a withering machine gun

fire.

The plan for the raid contemplated

that the raiders would strike due north until the road from Sebastopol Farm to

Pagny was reached, the men from the 179th Brigade then turning west and

returning by the light railway, while the detachment from the Texas Brigade was

to turn east along the valley south of Bois de Beaume Haie and circle

Preny. In keeping with this scheme of

march, the artillery barrage was also to execute a “column right” or “column

left.” For six hours prior to the attack, army corps and divisional artillery

harassed circulation and assembly points with gas and high explosives. The 37mm. platoon of the 359th Infantry

fired 600 rounds on Preny. The barrage

was timed to advance at the rate of 100 meters in 2½ minutes. The infantry found it impossible to keep up

with this speed. This fact enabled the

German machine gunners to crawl out of their concrete pill-boxes after our

artillery had passed over and set up their guns to catch the advancing

infantry.

The enemy defenses which the raiding

party encountered were all that the name “Hindenburg” implies. In the walls of Preny itself were several

concrete machine gun emplacements, and dugouts in the town were capable of

accommodating a large garrison. There

was a row of concrete pill-boxes at intervals of one hundred yards along the

ridge running west from Preny. Machine

guns from these positions, as from the woods to the north and west, completely

dominated open space across which the raiders were forced to pass. There were two lines of trenches: the first,

Tranchée des Grognons, and the second, Tranchée des Pepinieres, each defended

by bands of wire. The men were not able

to get beyond Tranchée des Grognons, and only a few reached this position. None who reached it came back to tell the

story. Captain David Vanderkooi,

Company F, 359th Infantry, sent a message that he had reached this trench, and

was not seen again, being wounded and captured.

The leading companies, after

suffering severe casualties, retired to the jumping-off position, and at 9: 50

A. M. orders were given to hold this position against counterattack, as the

enemy had followed up our withdrawal aggressively. The 343d Machine Gun Battalion had been moved to Côte 327 to lay

down a barrage on Preny and vicinity, and to be in readiness to meet this anticipated

counterattack. The battalion suffered

from artillery fire, Lieutenant Walter B. Dryson being killed.

Every company officer of the 359th

Infantry going into the action was a casualty, and during the day the 2d

Battalion, 359th Infantry, had five commanders. Captain Fred N. Oliver was wounded by shrapnel fifteen minutes

after the action began. He sent word to

Captain Vanderkooi to take command, but Captain Vanderkooi probably never

received the message. Lieutenant F. B.

Ferrais held the command a short time, remaining on the job despite a wound in

his neck by a machine gun bullet. After

the action, Captain Merlin M. Mitchell, Company M, was sent to take command of

the 2d Battalion, but on his arrival a shell burst directly in front of him and

he was sent to the hospital badly gassed and shocked. Captain B. M. Whitaker then commanded until the battalion

returned to Griscourt for rest, where

Captain Tom G. Woolen was placed in command.

Five officers of the 359th Infantry

were missing after the action. Two of

these, Lieutenants John C. Boog, Company F, and Oscar Nordquist, Company H,

were later known to have been killed.

CaptainVanderkooi, Lieutenant Walter J. Wakefield, Company F, and

Lieutenant James B. Morgan, who commanded Company H, were discovered in a

German hospital at Metz after the armistice.

CaptainVanderkooi was shot through the right arm and shoulder;

Lieutenant Wakefield had a bad wound in his lungs, and Lieutenant Morgan had

been so badly mauled by high explosive that it was necessary to operate on him

five times. Lieutenant Oscar C. Key,

Company C, was killed, and Lieutenant Lewis J. Hennessey, Company A, was

wounded. Both of these officers had

been attached to the raiding companies for the operation. Lieutenant Clifford Clower received a wound

which later made the amputation of one leg necessary. In addition, Lieutenant Leland F. Zilman, who was in command of

the combat patrol between the 359th Infantry and the 358th Infantry, was shot

in the leg. Lieutenant Claude W.

Fisher, adjutant, 2d Battalion, and Lieutenant Peter E .McKenna, battalion

intelligence officer were lucky enough to return with only slight scratches.

The raid also robbed the 358th

Infantry of one of its best officers, Captain Herbert N. Peters, who was killed

while commanding Company D. Lieutenant Robert E. Gilbraith, Company A, attached

to Company D for the raid, was wounded and captured. Lieutenant T. J. Devine, Captain Danenhour’s adjutant, received a

fractured shoulder from machine gun fire.

In the 360th Infantry, Lieutenant

Raymond C. Campbell, Company F, was very severely wounded and captured. He died of wounds in a German hospital,

according to reports.

Lieutenant E. R. Warren, commanding

a platoon of Company C, 315th Engineers, attached for the operation, and ten of

his men were wounded.

Such was our part in the initial

phase of the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

The mission was to make a demonstration which would lead the enemy to

believe that an attack was impending, thus causing him to hold reserves which

he could not spare from the real point of attack. The Division succeeded in this mission.

The Germans retaliated by heavy

shelling, particularly with gas, the afternoon and night after the raid. There were many casualties in the outpost

position of the 357th Infantry. The

next day there was a mustard gas concentration on the line of resistance of the

359th Infantry, Company B, 345th Machine Gun Battalion, suffering very

heavily. The positions became so bad

that it was necessary to move out of them into new ones. Owing to the persistency of this type of

gas, it was never possible to occupy the gas-saturated trenches during the time

that the Division remained in the Puvenelle sector.

View of Bois des Rappes (on the left) and camouflaged

road (on the right),

being a portion of the ground over which the raid of

September 26 took Place.

One of the concrete machine gun emplacements which were

a part of the defenses of the Hindenburg line

west of Preny.

Similar emplacements were constructed at intervals of about 100 meters

along the

Tranchee des Grognons behind the camouflaged road

running west from Preny.

Two views of concrete machine gun emplacements built

into the wall around Preny.

There were a number of similar emplacements in the wall

as well as loopholes

constructed in the walls of the buildings so as to

cover the valley south of Preny.

RELIEF BY THE 7TH DIVISION

THE 7th Division relieved the 90th Division during the

period of October 8-10, the command passing at 11 P. M., October 10. The 14th Infantry Brigade took the place of

the 179 th Brigade: the 34th Infantry, of the 358th Infantry; the 64th

Infantry, of the 357th Infantry; the 13th Brigade, of the 180th Brigade; the

55th Infantry, of the 359 Infantry: the 56th Infantry, of the 360th Infantry;

the 5th Engineers, of the 315th Engineers: the 10th Field Signal Battalion, of

the 315th Field Signal Battalion; and the 19th Machine Gun Battalion, of the

343d Machine Gun Battalion.

The area to which the Division moved

on coming out of line was practically the same as that which had been used for

staging purposes on moving from Aignay-le-Duc into the line. Battalions were billeted in practically the

same towns as before: Division Headquarters, the 315th Engineers, the 315th

Field Signal Battalion, and the Headquarters Troop, however, went to

Lucey. The distance from the front line

to the new area was so great that the troops staged two nights en route,

stopping the first night at the camps in the Puvenelle woods or around

Martincourt, the second night being spent in the half-way towns at Avrainville

and Francheville.

Intimations that something was in

store for the Division were conveyed by the corps order that the relief must be

completed and all units assembled in the billeting area by noon of the

12th. In order to carry out these

instructions, it was necessary to send trucks to Griscourt the morning of the

12th to move the personnel of Company C, 345th Machine Gun Battalion, the last

unit to be relieved. This company was

doing duty in the front line with the 359th Infantry, and was not relieved the

night of October 11, as was intended, owing to the fact that the corresponding

unit from the 7th Division became lost in the woods. Hence it was necessary for the company to get out in the

daytime. However, they safely filtered

across “Death Valley” before night, and went into billets at Griscourt.

View showing French tanks passing through Rampont.

MOVE TO BLERCOURT AREA

UPON coming out of the Puvenelle sector, every one eagerly

looked forward to an opportunity to rest, wash, clean up, and obtain badly

needed clothes and equipment. The men

who stumbled along, half asleep after nights of front line duty, down the smooth

Dieulouard road, which extended straight as an arrow, but apparently for an

interminable distance toward Toul, heard the sounds of the guns gradually

becoming fainter, and they dreamed of soft beds of straw in some French barn at

Domgermain or Pagny-sur-Meuse, where they could stretch out and sleep forever.

But this was not the time to

rest. The American High Command, fully

acquainted with the factors which were rapidly weakening the enemy resistance,

had determined not to lose a minute, and were pressing the attack in the

Meuse-Argonne sector with every available resource. The 90th Division, which had proved its capabilities in the St.

Mihiel attack, had been withdrawn, not to rest, but to take station at the

“post of honor” on the Meuse.

Therefore, before the last units had reached the staging area west of

Toul, orders were received to move by “bus” to a region west of Verdun.

A bus is a sort of truck fitted with

two long benches, and is designed to carry fifteen men. The busses were formed in a long train,

which moved from station to station under orders of the French C. R. A.

(Automobile Regulating Commission), exactly similar to a railway. On October 13 the 179th Brigade was moved to

the new area, passing over the famous Verdun-Bar-le-Duc highway, one of the

best roads in France, which was the sole route for supplies in the Verdun

defense after all railways were cut by Boche artillery.

Sudden changes in the military

situation brought about three different changes of orders regarding the

destination of this brigade during the period of eight hours that it was en

route. But the busses finally came to a

standstill near Blercourt, new division headquarters, on the Verdun-Chalons

road, twelve kilometers west of Verdun, where the troops “debussed” – that is,

climbed off the trucks as fast as their stiff legs would allow them. As this entire region is crowded with

barracks constructed by the French during and after the fight for Verdun,

accommodations for the brigade were found in the Bois de Sivry, just north of

Blercourt, and every man was able to sleep dry, despite the fact that the rain,

which had already lasted for weeks, was still coming down in torrents and the

entire region was one sea of mud.

Then there came another change of

orders. Busses first intended to move

the remainder of the Division were diverted to transport the 91st and 37th

United States Divisions to the French front in Belgium, to follow up the

successes there, and it was not until October 16 that the 180th Brigade arrived

and was billeted in barracks at Jouy, Rampont and neighboring camps. In the meantime, the motor and horse

transport of the Division, which had come overland in two separate convoys, had

arrived on the scene.

View of Esnes, showing blocked traffic moving at the

rate of only two 2 miles per hour.