THE BATTLE PERIOD

CUTTING OFF THE ST. MIHIEL SALIENT

RELIEF OF THE 1ST DIVISION

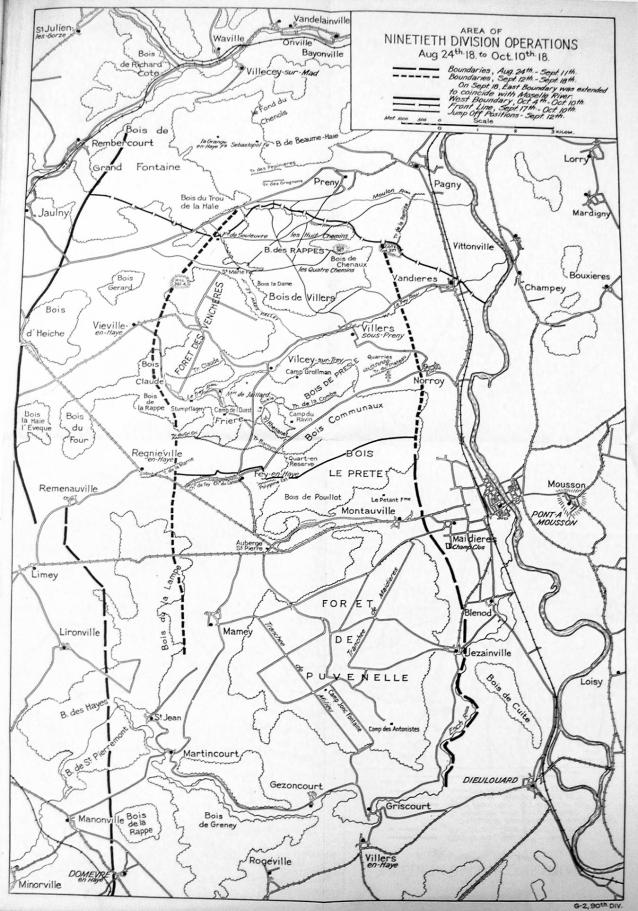

THE sector where the Texas and

Oklahoma men first entered the battle-front was almost due north of Toul. The right boundary of the Division was about

two kilometers west of the Moselle River, the front line beginning at a point

in the Bois-le-Pretre about three kilometers northwest of Pont-B-Mousson, and extending more than nine kilometers

westward to a point just south of Remenauville. There were German outposts in the ruins of the last-named

village.

The 90th Division relieved the 1st

Division, a regular army organization which was the first American division to

enter the European battle-front. This

famous division had already made a name for itself, and at the time of the

relief its ranks were sadly depleted by casualties incurred in recent fighting,

particularly in the thrust at Soissons on July 18, where the division had

captured the heights above Soissons and also the town of Berzy-le-Sec. Some of its companies were commanded by

sergeants. Major-General John P.

Summerall, who had formerly commanded the 1st Field Artillery Brigade, was at

this time commanding the division.

General O'Neil's brigade relieved

the 1st Brigade, with headquarters at Martincourt. The 1st Brigade was commanded at this time by Brigadier-General

John L Hines, who later became a Major-General and commanded in turn the 4th

Division and the 3d Army Corps. He had

come to France on General Pershing’s staff as a major, later taking command of

the 16th Infantry.

Colonel Hartmann’s first P. C. was

at St. Jean, his regiment relieving the 16th Infantry, which held the open

ground southeast of Remenauville and the thick woods at the head of the valley

of the Esch, a little stream which wound its tortuous course, first southward

through St. Jean and Martincourt, then turning eastward through Gezoncourt and

Griscourt, and finally bending northeastward, passing by Jezainville before

emptying into the Moselle at Pont-B-Mousson.

The 18th Infantry was replaced in

the trenches along the high, open ground behind Fey-en-Haye by the 358th

Infantry. Colonel Leary establishing

his P. C. in some barracks forming a part of the huge Camp Jonc Fontaine in the

heart of the Puvenelle forest. Just

across the roadway was established the P. C. of the 359th Infantry, commanded

by Colonel Cavenaugh, which had relieved the 28th Infantry.

The 2d Brigade was commanded by

Brigadier-General Beaumont B. Buck, who started his career at Dallas,

Texas. General Buck was later promoted

to major-general and put in command of the 3d Division. His P. C. was at Griscourt when relieved by

General Johnston.

The

two regiments of the 180th Brigade took over the trenches running through

Bois-le-Pretre, the famous woods which had been the scene of desperate fighting between the French and

Germans in 1915. The action which occurred there was typical of the bitter

trench fighting which characterized the year 1915 in the history of the World

War. The trenches of the opposing

forces were so close together that an ordinary tone of voice in the German

trenches would be audible to the French.

The struggle never ceased, and the harassing by artillery, hand

grenades, machine guns, and raiding parties continued day and night. A gain of a few yards was sometimes

warranted of sufficient importance to receive notice in the official

communiqué. During this period what had

once been a dense forest was reduced to nothing more than a waste of stumps.

As

the sector quieted down, the Germans and French drew further apart, leaving a

wide No Man’s Land. At the time the

90th division entered the sector, No Man’s Land was of an average width of one

kilometer, and was filled with the maze of trenches and wire which was once a

part of the front line systems. In this

drawing apart, the ruins of the villages of Regnieville and Fey-en-Haye were

left unoccupied between the contending forces.

The 360th Infantry relieved the 26th

Infantry on the extreme right, and Colonel Price’s first P. C. was in a quarry at about a kilometer

southwest of Jezainville.

Since 1915 this sector had been

quiet. It took the name of Saizerais

from the town which was occupied by the P. C. of the division in the line. After spending two weeks in the Saizerais

sector, the 1st Division withdrew to the Vaucouleurs area to receive

replacements before taking it place on the extreme left of the American forces

in the battle of St. Mihiel.

The relief was made by one battalion

of each regiment entering the front line, another battalion taking a position

in support about four kilometers from the front line, and the third battalion

of each regiment being in brigade or division reserve further to the rear. A machine gun company was attached to each

battalion.

The 3d Battalion, 357th Infantry,

was the first battalion to enter the line.

Its relief was reported complete at one o'clock on the morning of August

22. On the two preceding nights the 3d

Battalion had stayed at Francheville and Martincourt, respectively. The 2d Battalion, 359th Infantry, entered

the front line the same night, the relief being completed only shortly after

that of the 3d Battalion, 357th Infantry.

Also that night the 2d Battalion, 358th Infantry, and the 1st Battalion,

360th Infantry, went into positions on the main line of resistance.

The 3d Battalion, 358th Infantry,

and the 2d Battalion, 360th Infantry, entered the front line the night of

August 22-23, the main line of resistance being occupied that night by the 2d

Battalion, 357th Infantry, and the 1st Battalion, 359th Infantry. The following night the relief was completed

by the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry, taking reserve position at Martincourt;

the1st Battalion, 358th Infantry, moving up to reserve at Francheville; the 3d

Battalion, 359th Infantry, occupying its reserve position at Villev St.

Etienne, and the 360th Infantry reserve battalion, the 3d, taking up position

in Camp des Antonistes, in the southern end of ForLt de Puvenelle.

The

1st Field Artillery Brigade covered the front of the 90th Division until, on

August 28, it was relieved by the 153d Field Artillery Brigade (78th Division).

A blocked camouflaged road guarded by Americans

on the outskirts of Pont-B-Mousson, one kilometer

from first line trenches.

Bridge over the Moselle River connecting Mousson and Pont-B-

Mousson, france. This bridge was under constant

German observation and fire.

Metz bridge. Both lower and upper roads were used continually

during the big drive. The 357th infantry had dumps of rations,

ammunition and gas supplies near this point

View of Rue Victor Hugo, Pont-B-Mousson, from railroad station, showing

effect of shell fire. Pont-B-Mousson was located just off the

right flank of the sector occupied by the 360th infantry.

RUMORS OF COMING OFFENSIVE

THE period of the Division's

history from the time of first entering the line to the general attack on

September 12 can best be considered in connection with the St. Mihiel operation,

as this was merely a period of preparation.

The plan for the long-awaited, much-talked-of ‟big American

push" – on which the Allies had based all their hopes – had already taken

concrete form: and, in fact, it may be said that it was in accordance with this

plan that the 90th Division took its place in line, just west of the Moselle.

While the coming operations were

guarded with the utmost secrecy, every change pointed unmistakably to the same

conclusion. At the very beginning, for

example, headquarters of the 90th Division was pushed forward to

Villers-en-Haye, instead of remaining at Saizerais, the P. C. of the 1st

Division, and Saizerais was taken by the 1st Army Corps, which had replaced the

32d (French) Army Corps, headquarters at Toul, which had long commanded the

sector.

It was evident that the exhausted

French divisions were not being replaced by fresh American troops for no

purpose. The first operation report

issued by G-3, 90th Division, read: “Quiet. N. T. R.” N. T. R. is the abbreviation

for ‟Nothing to report.” But more stirring times were soon to come.

At this time there were still a

number of civilians in Villers-en-Haye, who, after four years of war,

recognized the signs of the coming offensive more readily than the Americans,

who were still inexperienced in the arts of modern war. It requires more than a big offensive to

drive the French peasant from the humble home where his family has lived for

generations. Throughout all the

preparations the farmers of Villers continued to go calmly to the fields every

day. The hostile bombing often

disturbed their slumbers at night, and drove the family to the “cave” or

cellar, but they had become accustomed to such inconveniences.

Although the tentative draft of the

1st Army Corps field order was not issued until September 6, on which date the

offensive was officially made known to the divisional staff, long before this

time mysterious rumors, which are a part and parcel of military life, filled

the air and furnished authoritative material for doughboy, “boards of

strategy.” In all these vague surmises the name of the fortified city of Metz

was the magic word which dominated the minds of all. “Big push,” “American offensive,” “Capture Metz,” were the

phrases heard wherever as many as two soldiers came together. They were whispered by sentries on post in

trenches nearest that historic fortress, and back in the rear areas such

military strategists as hospital orderlies discussed the probable effects of

the fall of the formidable circle of forts surrounding the city on the eventual

breakdown of the Western front.

But

Metz was not the objective of this first operation of Pershing's army. And had that city been the objective, as it

was one objective of an operation fully prepared but rendered unnecessary by

the signing of the armistice, the plans would not have called for a direct

attack, but rather an outflanking movement on either side. Such was the idea of the unfought battle of

November 14, 1918.

Street Scene in Villers-en-Haye. The 90th Division P. C. was located

in the square building which is seen just under the church steeple.

FIRST EXPERIENCES IN THE TRENCHES

IN order to mask the coming

attack, the sector was kept a ‟quiet” one. Until the time that the Division began active preparations, the

only activities were the usual artillery fire, the daily airplane patrol, and

patrol reconnaissances. But those

nights in the front line trenches, with nothing separating the occupants from

the Boches but terrifying blackness which occasionally took on living form,

will long be remembered after more spectacular moments are forgotten. Since the Division had taken over a front of

more than nine kilometers, the troops in the outpost garrisons were necessarily

widely dispersed. There were naturally

some cases of ‟nervousness,” which were given vent in rifle or machine

gun fusillades, or in calls for an S. O. S. barrage from the supporting

artillery, but it is hard to find fault with over-caution.

Until September 12 the total battle

casualties were only ten fatalities, thirty-nine wounded, and one missing. The first members of the Division to give up

their lives were Lieutenant Richard H. Graham and Sergeant Walter Burke,

Company F, 360th Infantry, who were killed about midnight of August 24-25 by

the accidental discharge of a hand grenade.

This fatal grenade was probably one of the thousands of old French ones

which were strewn throughout the front areas, being piled in the mud in the

corners of trenches, hidden away in niches cut in the walls or scattered along

the top of the parapet.

The first patrol to leave the 90th

Division lines was led by Lieutenant Edwin D. McCoy, 3d Battalion, 357th

Infantry, who took up a position the night of August 22-23 in an old French

trench – de la Marne – just east of Regniéville, for the purpose of ambushing

German patrols which were suspected to be operating in that vicinity. The 357th Infantry also boasted the first

prisoner, a deserter from the 332d Regiment of the 77th Reserve Division. Incidentally, it was from the 357th Infantry

that the first man of the 90th Division was captured by the Germans. A private of Company K was spirited away

from an outpost just south of Regniéville about 8:30 o'clock the morning of

August 23.

Each regiment sent a patrol out to

its front nightly to locate the enemy outposts and ascertain the nature of the

hostile defenses. This also served the

purpose of acquainting the men with No Man's Land, over which they were later

to advance. Some of these patrols had

stirring adventures. On the night of

September 8 Corporal William R. Ball (who died of wounds received at Huit

Chemins two weeks later) and Private Andy Keeton, both of Company G, 357th

Infantry, became separated from the other members of a patrol, and in the

darkness ran into a force of Germans estimated at fifty. They succeeded in holding off this force and

in killing or wounding eight of them.

Both soldiers were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

During these days the officers in

the front, and even in the support and reserve positions, were worried, day and

night, by inspectors. Existing orders

of the ‟Plan of Defense,” inherited along with the sector, required an

officer of the division staff to inspect one front line company nightly. This officer of the division staff went

forth with a series of questions covering every conceivable subject. Then there were corps inspectors, army

inspectors, G. H. Q. observers, inspectors from the gas service, the medical

department, and plain infantrymen.

Ordnance experts counted the

number of caterpillar rockets in company pyrotechnic dumps and inquired why there were only a

half-dozen three-star ones on hand; G-1’s inspected the front trenches in their

zeal to ascertain the number of tins of reserve rations to each kilometer of

front, ammunition on hand, and condition of the men.

While the preparations were going

forward, Brigadier-General William H. Johnston received his promotion as

major-general and was ordered away to command the 91st Division. Brigadier-General U. G. McAlexander, who, as

colonel of the 38th Infantry, had won

the French Croix de Guerre with Palm and the

D. S. C. on the Marne against the great German attacks of July 15, 1918,

and in the counter-attacks, took

command of the 180th Brigade on August 27.

When the 1st Division was originally

organized General McAlexander was attached to the 16th Infantry and arrived

with it in France, June, 1917. He

was later assigned to the 18th

Infantry, whose colors were the first American infantry colors to appear on the

French front lines, November, 1917. On

May 14, 1918, General McAlexander

joined the 38th Infantry – the regiment with which his name became linked under the sobriquet of

“The Rock of the Marne.”

General McAlexander was born at

Dundas, Minnesota, August 30, 1864. He

graduated from West Point in 1887. His

services in campaigns before the European War included those against the

Indians during the winter of 1890-1, the

Spanish-American War and Cuban campaign in 1918, and the Philippine

insurrection of 1900. He graduated from

the Army War College in 1897.

Strangely

enough, simultaneously with the offensive preparations, a large proportion of

the engineering regiment was engaged in preparing defensive works. Before American troops had taken over the

sector the French had decided upon and

began work on a new line of resistance about four kilometers from the front,

called “Position 2 Bis,” extending from the Moselle River at Jezainville in a

westerly direction through the Puvenelle forest to St. Jean; and also upon a

bar rage position near Francheville.

These positions had already been marked out, and work done at various

points on trenches, wire, dugouts, emplacements, and concrete pill-boxes.

The engineering companies were distributed along Position 2 Bis

from east to west, as follows: Co. F,

Co. E, Co. D, Co. A. Company C worked

in the Francheville area until

September 8, when it moved to St. Jean.

Company B was assigned to road work, and was assisted by infantry

working parties.

From

September 6 until the attack there was a continual shifting and moving of organizations. On that date the P. C. of the 179th Brigade moved from

Martincourt to Gezoncourt, and the advance echelon of the 5th Division went

into Martincourt. The attack order

provided that the 5th Division would take over a front which, in width,

practically corresponded with the subsector of the 357th Infantry. The 2d Battalion, 357th Infantry, remained

in the outpost position opposite Regniéville until the night of September 11 to

make sure that the enemy could not secure any new identifications and thus

learn of the concentration of troops on this

front. However, all other elements

of the regiment were relieved prior to that time. On the night of September 8-9, the reserve elements

“side-slipped” to the east, and 5th

Division troops moved into the shelters thus vacated. The following night the

relief on the support position took place.

During

this period the “rear echelon” of the Division was also pushed forward so that

by the time of the attack no units were rear of Villers-en-Haye. On September 8 the railhead moved from La

Cumejie (two kilometers west of Manoncourt) to Belleville on the Moselle; the

offices of the inspector, judge advocate,

and billeting officer shifted to Villers-en-Haye; and the 315th Sanitary

Trains established their P. C. at Griscourt instead of Rosieres-en-Haye.

PREPARATIONS FOR BIG ATTACK

THE scene which the divisional

sector presented during those last days of preparation was one that beggars

description. There was not a nook or

cranny, in the woods, behind a ridge, under the cover of a quarry, that did not

conceal a battery, a tank, an ammunition dump, a depot of engineering supplies,

or, perhaps, a battalion of infantry.

The huge ForLt de Puvenelle, which seemed to cover half of the

divisional area, was alive with the materials of war. A ride down the Tranchée du Milieu and the Tranchée de Maidieres,

roadways which bisected the dense forest, might truly be compared to a visit to

a museum in which had been collected and parked for convenience of inspection

all the latest inventions of the military art.

While no tanks participated on the

front of this Division, the woods within the sector were used as a staging area

for the whippets which were to lead the assault for the 5th Division. Heavy artillery units, both American and

French, began arriving at an early date.

Gigantic guns of 9.2-inch caliber waddled in during the night, and by

morning were in a neatly camouflaged position at one side of the road, with the

crews sound asleep in the mud beside them.

Sometimes, however, daybreak still found them a long way from their

destination – perhaps it was engine trouble, perhaps the slippery roads – but

at all events there was only one thing to do, and that was to scurry to the

nearest cover before the German aviators came over on their dawn patrol. The favorite locality for these monsters was

along the Gezoncourt-Martincourt road, behind the cover of the strip of woods

which followed the road on the north, and in the valley of the Ruisseau d’Esch,

which ran north and south through Martincourt.

The men to whom should go much

credit for valiant service during these nerve-racking days are the drivers of

the motor trucks of the 315th Supply Train.

Of necessity, all traffic was under cover of night. And such nights! The volume of rain, which had been falling steadily for weeks,

increased as the day approached. The

slippery roads were jammed with artillery, trucks, horse transport,

automobiles, marching troops, tanks, and on the edges motorcycle messengers

bearing important orders picked their precarious way. Of course, no lights were allowed, and the drivers had to follow

the muddy, jolty, treacherous roadway as their ‟sixth sense” directed

them. All would go well until a long

string of trucks met, head on, a similar convoy from the other direction; then,

in the attempt to make the passage, a truck with its heavy load would “stick”

or go in the ditch, and all traffic was suspended until the machine could be

ejected. Often this was out of the

question, and the best that could be done was to push it as far out of the path

as possible and abandon it.

A source of great trouble was a

steep hill with a sharp turn at the top, just on entering Gezoncourt from the

direction of Griscourt. The grade was

so pronounced that wheels could not stick to the slippery surface. As the vehicles could not make the ascent

under their own power, it was necessary for the men themselves to push the

machines through. The descent from

Villers-en-Haye to Griscourt was also a source of trouble. It was necessary to build an entirely new

bridge across the little stream that runs through Griscourt in order to allow

the tanks to pass and to accommodate the rapidly increasing traffic.

Many incidents occurred during these

tense days which later took on a humorous nature. Some French officers of a trench mortar battery, in their zeal to

obtain as advantageous firing position as possible, had pushed their mortars

out into No Man’s Land along the Montauville-Norroy road in the

Bois-le-Pretre. The Following morning,

when a sentry of the 360th Infantry was moving out cautiously to his day post

he came upon the Frenchmen. Naturally,

as the officer was beyond the outpost, he suspected him, and, to make the

situation worse, neither the Frenchman nor the American could understand the

other. The French lieutenant attached

to regimental headquarters settled the difficulty. Some American trench mortar crews also slipped through the

outpost and calmly took up a position in Fey-en-Haye, then in No Man’s Land,

and went to sleep!

Beginning the night of September

9-10, the artillery, under the command of Brigadier-General C. C. Hearn, 153d

Field Artillery Brigade, the divisional artillery commander, moved by echelon

into position.

The two battalions of the 307th

Field Artillery, which were to be in liaison with the 179th Infantry Brigade,

took up positions under cover of road embankments and patches of woods in the

neighborhood of Auberge-St. Pierre. The

308th Field Artillery, assigned to support the 180th Brigade, was placed in the

woods west of Montauville on both sides of the St.-Dizier-to-Metz highway. The battalions of 155’s composing the 309th

Field Artillery Regiment were along the northern edge of the ForLt de Puvenelle.

Three battalions of the 238th Field

Artillery (75’s), the 3d Battalion of the 183d Field Artillery (220 mm. and 155

mm.), and the 3d Battalion of the 282d Field Artillery (220 mm.), all French

personnel and materiel, as well as the 10th Battalion of French Trench

Artillery (58 mm., 150 mm., and 240 mm.), were under the divisional artillery

commander.

The 303rd Trench Mortar Battery

(6-inch Newtons) and the 1st Battalion of Trench Artillery (240 mm.) were in

line in the Bois-le-Pretre and Bois du Pouillot in the sector of the 360th

Infantry. Their mission was to cut

wire, and they were more successful than on any other part of the front. While the 360th did not advance on September

12 over the ground where the wire-cutting had been going on, it was valuable on

September 13. The principal difficulty

came in the matter of ammunition supply.

A carload of trench mortar ammunition drifted in on the tracks at Marbache,

in the sector of the 82d Division. This

was promptly secured, and the contents carried forward to the batteries.

The day before the attack the

artillery plan was changed to include four hours of preparation. This cut into the supply badly. All battery positions were supplied with

three “days of fire” before the attack, but some of it did not reach the

batteries until after the artillery action had opened.

In all the plans of the 1st Army,

surprise was the thing at which they aimed.

Of course, it was impossible to keep from the German intelligence

service the information that an attack of some sort was being planned. However carefully guns and material may be

camouflaged; however quietly and cautiously activities may be carried out under

the cover of night; despite the fact that every attempt be made to preserve the

normal appearance of the sector, and that the artillery be allowed no more than

its usual rate of fire, the big guns not even being allowed to register on

their targets, the fact of a coming operation cannot be absolutely camouflaged. However, it was possible to conceal the

exact point where the maximum effort would be made, so that the German high

command would not know where to place its reserves; and the exact day when the

attack would be launched also could be kept a secret. In attacking on September 12 the army undoubtedly sprang a

surprise which resulted very seriously for the Germans.

During the last few days before the

attack, front line battalions were engaged in cleaning out the old French

trenches in No Man’s Land from which they were to jump off on September

12. During three years of inactivity

these trenches had become filled with wire and trash. All the work had to be done silently, under cover of darkness,

and the trash had to be disposed of out of sight, as nothing reveals a contemplated

attack so readily as the preparation of a jump-off line, It was necessary to

prepare this departure position very carefully, as the rolling artillery

barrage was calculated to fall 500 meters in front of it, and mistakes would

mean “shorts” on the heads of our own men.

The Division battle P. C. was

officially opened at Mamey at noon, September 11. During the afternoon notification of H hour was sent out to all

commanding officers pressed delete, who were in turn charged with transmitting

the information to subordinate commanders.

The assembly of the infantry for the

attack was successfully accomplished in despite of difficulties. The night was as black as ink and the rain

was coming down in sheets. The

positions to be taken up were new to the men, in most cases, and to many of the

officers. After floundering about in

the mud, stealthily and without light the men took up their positions before

the opening of the artillery bombardment.

That artillery preparation was a wonderful thing! It may be doubted if all the firing,

terrific as it was, had any material value on our front other than to kill a

few Germans. Certainly it did not cut

any wire. But the sound of the shells

whizzing over their heads and the sight of the flashes of bursting high explosives

in Bocheland cheered the shivering men in the strange trenches and relieved the

strained of the long wait for H hour.

Some of the battalions made marches of considerable distance before reaching their positions. The 1st Battalion, 360th Infantry for example came into line from reserve in an old French camp called Camp des Antonistes in the southern end of the ForLt de Puvenelle. The 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry on the other flank of the attack, had a march of even greater length from the woods near Griscourt. The relief of the 2d Battalion, 357th Infantry, by the 5th Division did not begin until 11 P. M. but between that time and H hour Captain Lammons succeeded in making the relief and moving his companies into support position.

View of Villers-en-Haye (on the hill in the distance) and Griscourt. In order to relieve traffic

congestion across the stream, the bridge on the left was built by the 315th Engineers.

Dugouts at Mamey, where battle P. C. Of the 90th Division was located during the St. Mihiel

attack. P. C. Of the 179th Brigade was located here during the division

occupancy of the Puvenelle sector.

GENERAL PLAN OF THE BATTLE OF ST MIHIEL

JUST as the attack of September

12 was the first experience of the 90th Division in offensive tactics so it was

the initial attempt of the American Expeditionary Forces at large-scale

operations. Prior to that date American

divisions, and even corps, had played their part at critical moments along

different parts of the Allied line. But

it was not until the latter part of August that the training of all branches

had reached a point that made possible the organization of the 1st American

Army.

An

army, it must be understood is more than a collection of divisions. In the first place there must be a staff

accustomed to handling large-scale operations.

General John J. Pershing, commander-in-chief of the A. E. F., himself

took command of the army for this first operation. There must be railroads and lines of communication and depots of

supplies of all sorts and experienced officers who know how to get those

supplies forward to the fighting organizations. Then there is the aviation service, the tank corps, the long guns

of the artillery, the special gas and smoke troops, telephone battalions, the

increased medical personnel and hospitals and supplies, engineers to rebuild

the roads and railroads as the advance progresses not to mention the hundreds

of military police required for the control of traffic and the evacuation of

prisoners, and the salvage squads which reclaimed and saved the debris of

battle. In all there were about 216,000

American and 48,000 French troops in line and about 100,000 American troops in

reserve.

“The

First Army (U. S.) will cut off the St. Mihiel salient.” This sentence of the

field order for the operation tersely, definitely, unequivocally stated the

mission for which this huge army had been assembled on the famous battlefield.

Among

the reasons why this place was chosen for the first ‟show” of the

Expeditionary Forces are: First, this was a part of the front set aside as the

‘‘American sector”; secondly, the reduction of the salient would definitely

relieve the half-enveloped position in which Verdun was placed and would free

the important double-track Verdun-Toul-Belfort railway; and, lastly, the

straightening of the line would prepare the way for further operations in which

the great iron mines of the “Briey basin,” the German concentration point at

Metz, and the Montmédy-Sedan-Valenciennes railway, would be the stakes.

The attack was made by four army

corps. Two American corps were on the

south face of the salient. The 1st Army

Corps operated from Clemercy, east of the Moselle, to Limey, and the 4th Army

Corps extended the line to Xivray, where it connected with the 2d French

Colonial Corps. The French were at the

point of the salient, and were to follow up as the Germans withdrew. On the west face, with Les Eparges in its

center, was the 5th Corps.

The principle of the maneuver was

that the point of the salient would be pinched off by the junction of the

attacking forces from the south and the west in the neighborhood of

Vigneulles. The divisions on the south

face would attack at 5 o’clock A. M., the first day’s objective being a line

embracing Thiaucourt and the crests beyond the Rupt-de-Mad to Nonsard. On the second day the advance would be

pushed to Vigneulles, where connection would be made with the 26th Division from

the west, which was to make its original attack at 8 o’clock A. M. on September

12. By effecting this junction the

enemy’s line of retreat from St. Mihiel to Gorze would be cut off and the

troops remaining in the pocket would be “bagged.”

The German troops holding the

salient were of Army Detachment ”C,” Lieutenant-General Fuchs commanding, of

the army group of Von Gallwitz. From an

official report of Army Detachment “C” which has since come into the hands of

the American intelligence service, it appears that the German high command

hesitated too long in making up its mind whether to resist strongly all attacks

or withdraw from the salient. A strong

“Hindenburg line” called the ‘‘Michel position” had been prepared. At a conference of the commander of the army

detachment and the division commanders on the afternoon of September 10 it was

decided, according to this official report, to begin preparations for the

systematic evacuation of the salient.

It was estimated that a period of eight days would be necessary to

remove important war materials and supplies and to destroy important

works. This work of removal and

destruction began on September 11.

“This was the situation when the hostile attack was launched by surprise

on the night of September 11 and 12,” the report stated.

The

German troops of the Michel group – that is, in the point of the salient –

received the order that “the withdrawal will begin at once” at noon September

12. They were forced to make a

thirty-kilometer hike that night in order to get the bulk of the personnel

clear of the St. Benoit cross-roads before the 1st American Division cut their

line of retreat.

DIVISION AND BRIGADE PLANS

FOR ATTACK

THE 1st Army Corps, commanded by

Major-General (later Lieutenant-General) Hunter Liggett, was composed of five

divisions. Three divisions were to

attack: the 90th on the right, the 5th in the center, and the 2d on the

left. The 82d Division, which

straddled the Moselle River, was to hold on its front, and the 78th Division

was in reserve.

Thus it will be seen that this

Division was on the extreme right of the attacking forces; in fact, the

Division’s special mission was to protect the right flank of the advance. As the narration of events proceeds, it

will be possible to appreciate more fully the difficulties of the important

task assigned the men from Texas and Oklahoma who were going into their first

fight.

The situation was rendered even more

trying by the fact that the divisional right boundary ran along the heights

about two kilometers west of the Moselle.

The left boundary on this day ran north from Mamey, crossing No Man’s

Land 1500 meters east of Regniéville, through Bois de la Rappe, along the

Stumpflager- Viéville road up the valley that bisects Bois St. Claude: thence

around the western edge of ForLt des

Vencheres and Bois des Rappes to La Souleuvre Farm.

The divisional plan of attack was

set forth in Field Order No. 3, issued at 17 hours (i. e., 5 P. M.)

September 9, which prescribed that the brigades would fight side by side, and

that in each brigade the regiments would be placed side by side. Since the Division was the pivot for the

entire offensive, it was provided that the 180th Brigade, in the right

sub-sector, should merely hold on part of its front and make a limited advance

on the remainder of its front, while to the 179th Brigade fell the task of

pushing ahead on the left, so as to aid the advance of the 5th Division, and of

tapering off toward the right so as to connect with the old front line. Thus the line drawn on the battle map by

the army commander and called the “first day’s objective” required an advance

to a depth of four kilometers on the extreme left of the 90th Division sector,

a gradually diminishing advance on the remainder of the front of attack, and no

advance at all on 2½ kilometers of the Division front. The width of the divisional front on this

day was about six kilometers.

On this secret battle map there was

also marked another line in black, called the “exploitation line.” It was the

army plan that the first day’s objective, upon being captured, should be

strongly organized as the main line of resistance of a new defensive position;

that on the second and following days the ground between the first day’s objective

and the exploitation line should be seized, and the American outposts

established along this exploitation line.

Roughly, the exploitation line was parallel to the German Michel

position. Hence the theory of the

exploitation line was that the enemy would not stop his withdrawal, after his

first defensive positions had been broken, until he arrived at this strong

Michel line; and that the victorious American troops should seize all the

ground possible while the hostile forces were in a state of demoralization.

It will be seen later on, however,

that the “exploiting” of the 90th Division did not stop on this original line,

but was continued to include important heights on the west bank of the Moselle.

The preparation of the orders for a

‟trench warfare” attack is a monumental task. The working out of the infinite details was the task of the

General Staff and of the heads of technical services. A good staff officer must not only have a knowledge of staff

technique, but must also possess a never-wearying faithfulness to duty and a

willingness to sacrifice himself for the welfare of the entire command. Success in modern warfare is impossible

without excellent staff work, no matter how intrepid the officers, how

courageous the men. The staff of the

90th Division, as well as the fighting ranks, proved itself in its first big

effort.

It

may be said that the excellence of staff work can be tested by the results

accomplished with the least sacrifice of lives and the elimination of useless

effort on the part of the soldiers.

The staff of the 90th Division worked overtime in order to achieve this

standard; and the fact that it was successful may be attributed to the

self-effacement and spirit of cooperation which inspired its members. The chief of staff, Colonel John J.

Kingman, a model of coolness, suavity, and efficiency, set a high standard for

all others.

The

secrecy surrounding the St. Mihiel operation handicapped the staff by the fact

that only a very short time was available for the completion of plans. And here are just a few of the things that

had to be done:

First, before the attack order could

be written, it was necessary to find out everything possible about the

enemy. This job was done so thoroughly

by the intelligence department under the direction of Colonel Tatum, assisted

by Captain (later Major) James C. McManaway and Lieutenant Maurice B. Deschler

of the Corps of Interpreters, that with remarkable accuracy the location of every

German unit down to squads on outpost was forecast. The location of trenches and strong points and the strength of

their garrisons, the position of machine guns and trench mortars, the enemy

camps, principal roads, telephone centrals, supply depots, etc., were

determined and indicated on intelligence maps. The infantry needed this information in planning its maneuver;

it was essential to the artillery so that the “big stuff” could be dropped

where it would “do the most good.” Prisoners and deserters also revealed the

enemy order of battle and the quality of the opposing troops.

The task of the Operations Section had only begun on the

completion of the three and a half typewritten pages of Field Order No. 3. It was necessary to coordinate the innumerable

‟annexes” which prescribed the duties of the artillery, signal troops,

air service, engineers, smoke and gas troops, and the like. As Colonel Thorne joined the staff of the

1st Army shortly before the operation, this work fell to Major Andrews. With his characteristic thoroughness he

went to the bottom of every arrangement to see that no stone was left unturned

which might contribute to success. His

assistants throughout both this drive and Meuse-Argonne offensive were Captain

(later Major) George Wythe, Lieutenant (later Captain) Daniel H. Kiber,

Lieutenant (later Captain ) J. P. Mudd, and Lieutenant J. P. Kennerley.

The sixteen typewritten pages of the

annex on ”Communications, Supply, and Evacuations” furnish some clue to the

multitude of matters directed by Colonel Murphy and his staff of assistants in

the G-1 office.

In addition to supervising the

somewhat routine matters handled through the division adjutant, division judge

advocate, division inspector, and division veterinarian, and the supplying of

animals, motor and animal drawn vehicles, ammunition, quartermaster and

ordnance supplies. G-1 was responsible

for the planning and execution of numerous elements entering into active

operations. The delivery of supplies,

involving the use of the 60-cm, railroads, the use to be made of trucks, the

questions of two-way and one-way roads, designation of road circuits,

establishment of ammunition and food dumps, of ration distributing points, of

traffic control, of evacuation of the wounded, burial of the dead, salvaging of

property, of constructions and repairs, all had to be considered, not alone

prior to the operations and during them, but also the means of handling these

matters and solving anew these questions after the offensive had terminated.

Colonel Murphy’s intimate knowledge

of every detail of supply and administration peculiarly fitted him for the task

of coordinating the work of the services.

His first assistant was Captain (later Major) Sylvan Lang, formerly of

Company L, 357th Infantry, who had finished the Staff College course at Langres

and received some practical experience with the English and the 3d Corps. Captain (later Major) Peter P. Rodes,

Lieutenant (later Captain) Ward Delaney and Lieutenant William R. Kincheloe were

the other officers of the First Section.

This is the way in which the

infantry brigade commanders drew up their plans for attack: General O’Neil gave

the 357th Infantry the position on the left, the regiment to attack with one

battalion in the front line and one in support, while the remaining battalion

was to take position in brigade reserve in the northwest corner of the ForLt de Puvenelle about one kilometer east of Mamey. Colonel Hartman chose the 1st for his

assault battalion and the 2d for support, the 3d going into reserve. The regimental sector was made narrow owing

to the fact that the depth of its advance was the maximum for the

Division. The jump-off position was an old trail just north of

Chemin de Fey. The regiment was to

traverse an open space of about a kilometer and a half before reaching the Bois

de la Rappe: then across a ravine which separated the Bois de la Rappe from the

Bois St. Claude: thence through the latter woods and winding up in another open

space just east of Viéville-en-Haye (the town in the 5th Division sector).

The 358th Infantry was given

approximately twice the frontage of the 357th Infantry, as it had a shorter

distance to go. Two battalions were

disposed of on its 1500-meter front.

The 3d Battalion, on the left, went over the top from some ancient trenches

north Tranchée du Calvaire, its right joined up with the left of the 2d Battalion

just in the center of the one-time village of Fey-en-Haye, the 2d Battalion’s

departure position being to the right of the town. The entire sector of the 3d Battalion was wooded from a point

about 750 meters from the assault line to the objective. A deep ravine ran due north in the center

of its sector to the objective, where it emptied into the valley of the Trey

brook. This same wood, the Bois de

Friere, extended into the northern part of the area assigned the 2d

Battalion. The 1st Battalion went into

support just south of Fey-en-Haye.

General O’Neil established his own

P. C. in a dugout in the woods at the side of the road running from Auberge St.

Pierre to Fey-en-Haye, about 800 meters northwest of Auberge St. Pierre. The 358th Infantry was near by, and Colonel

Hartman was about one kilometer from his jump-off line near the Auberge St.

Pierre-Regniévilie road.

General McAlexander placed the 359th

Infantry on the left of the 180th Brigade to link up with the 358th

Infantry. The 3d Battalion, the

assault unit, was to leave from Polygone Est trench. Its objective was a limited one, the most important feature

being the highly organized bit of ground where woods had once existed, known as

the Quart-en-Reserve, a block about 300 meters square, which protruded from the

west edge of the Bois-le-Pretre. The

2d Battalion was to follow in support.

The 360th Infantry was to have two

battalions in line. The left one, the

1st was to follow up the advance on its

left by easing off the sharp pocket formed to the east of Quart-en-Reserve and

connect with the 3d Battalion, which was to hold the old trenches from a point

one kilometer east of Quart-en-Reserve to the eastern boundary of the Division.

The 1st Battalion, 359th infantry,

and the 2d Battalion, 360th Infantry, were in division reserve, together with

the 343d Machine Gun Battalion, they were located in the northern edge of the

ForLt de Puvenelle, under command of Major McCoy, 343rd

Machine Gun Battalion.

General McAlexander’s P. C. was in a

dugout in the woods to the rear of the St. Dizier-to-Metz highway, about one

kilometer northeast of Auberge St. Pierre.

The 359th infantry was in the Ravine in the Bois dri Pouillot, and the

360th was the Le Petant Farm, on the reverse slope of the hill northwest of

Montauville.

Judged in comparison with the Meuse-Argonne operations, the artillery concentration for this attack was relatively insignificant. The creeping barrage was fired by nine batteries of American 75’s and nine batteries of French 75’s. Owing to the width of the front, this barrage was thin, at least in comparison with the 1000-meter deep barrage of November 1, north of Bantheville. The barrage lifted 100 meters at four-minute intervals, a rate which proved a bit too fast for the poor infantrymen who had to cross that sea of wire and trenches and kill a few Boches betimes.

When this barrage had gone forward

500 meters beyond the first day’s objective it stopped and fired so as to form

on this line a protective curtain.

Behind this rolling barrage bursts of fire from heavier calibers were

directed on “sensitive points” such as

communication trenches and machine gun positions. At H hour this “raking

fire” dropped on targets near the German front line, lifting as the infantry advanced. Fire for destruction was also carried out on the strong positions

in the Bois-le-Pretre, where stubborn resistance on the second day was feared.